In the November 9, 1998, issue of the New Yorker, in an essay that doubted whether Ernest Hemingway would have approved of the posthumous release of his unfinished book True at First Light (it would be published eight months later), the writer Joan Didion remembered with admiration and nostalgia the opening paragraph of his acclaimed (and finished!) novel A Farewell to Arms—“four deceptively simple sentences, one hundred and twenty-six words, the arrangement of which remains as mysterious and thrilling to me now as it did when I first read them, at twelve or thirteen, and imagined that if I studied them closely enough and practiced hard enough I might one day arrange one hundred and twenty-six such words myself.”

I would encourage you to take a look at those “one hundred and twenty-six such words” (again?) for yourself:

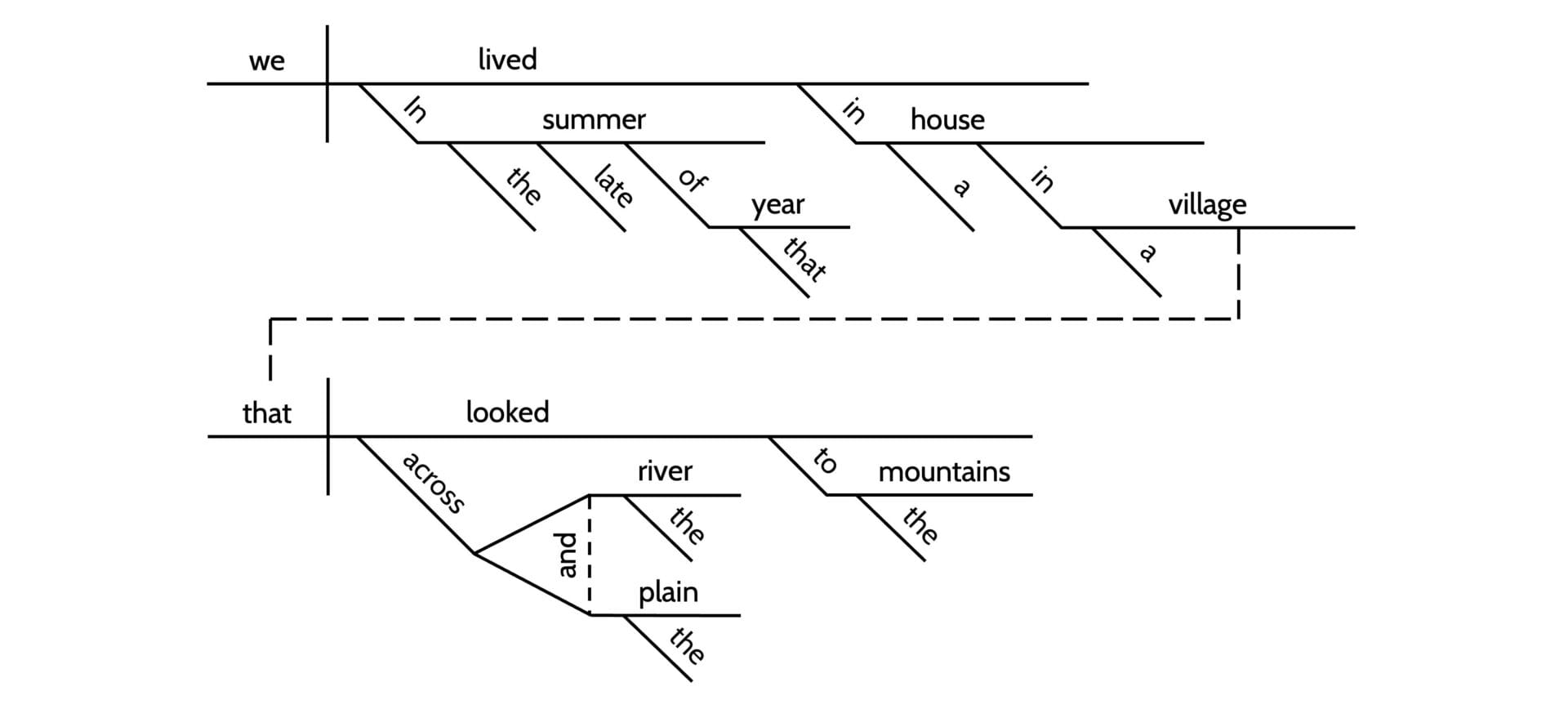

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

The apparent straightforwardness of Hemingway’s opening lines, in diction and structure alike, belies their actual inscrutability. Their nouns are sight-word basic (“summer” and “year,” “house” and “village,” “trees” and “leaves”) as are their verbs (“lived,” “looked,” “went,” “fell,” “saw”); and their childlike paratactical clauses (“and… and… and… and…”) weigh in at fewer than 1.2 syllables per word.

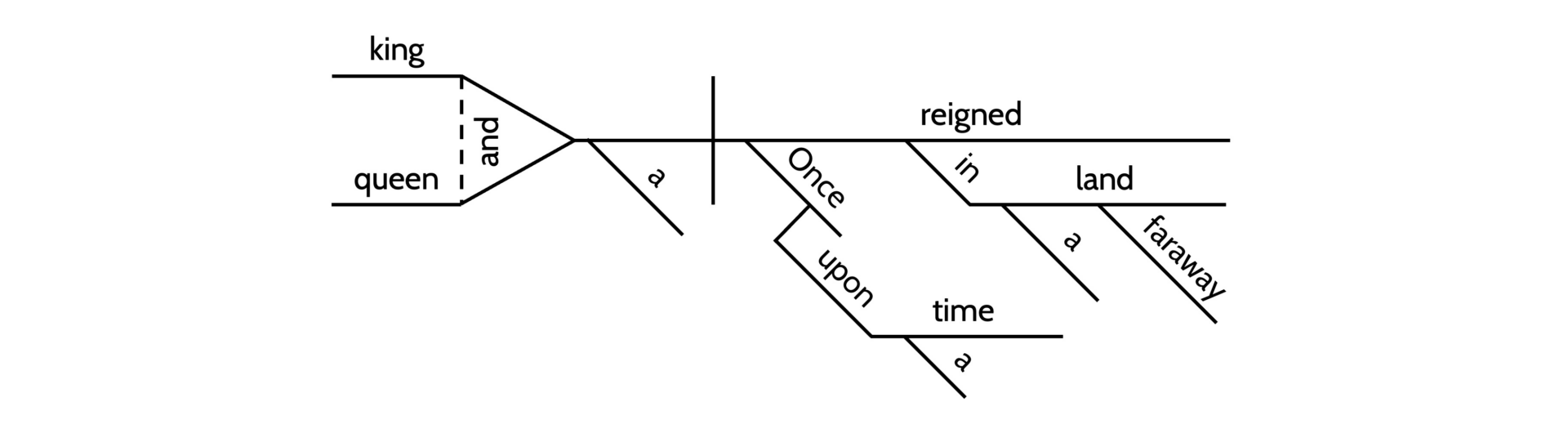

In contrast to the first-paragraph freight of other serious literature—that of Toni Morrison’s Beloved (with its “kettleful of chickpeas smoking in a heap” and 1.3 syllables per word) or Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (with its “Hollywood-movie ectoplasms” and 1.5 syllables per word) or Mary Ann Evans’ (aka George Eliot’s) Middlemarch (with its “yard-measuring or parcel-tying forefathers” and 1.6 syllables per word)—Hemingway’s airy, approachable beginning evokes that of a fairy tale. (“Once upon a time,” intones Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm’s version of Sleeping Beauty, “a king and queen reigned in a faraway land.”)

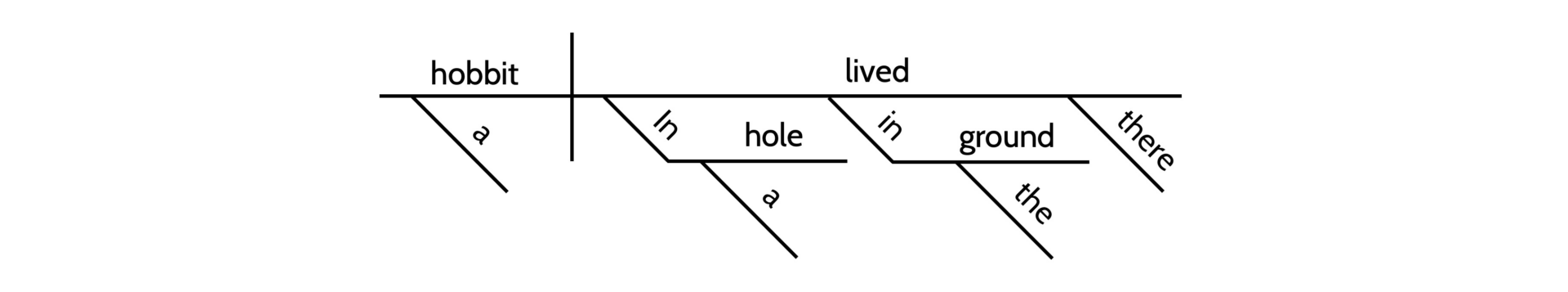

Adverbial prepositional phrases—especially when revealed diagrammatically, dependent from the verbs and adverbs that they modify—are the obvious predicate workhorses of both storybook beginnings, just as they are of the endearing opener of J.R.R. Tolkien’s first novel: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Simple adverbial phrases constitute the familiar singsong patter of fable—not to mention over 60% of the contents of the first two sentences of A Farewell to Arms. If we didn’t know better, we might mistake Hemingway’s novel for a children’s book.

With Tolkien, though, we know right away that we have chanced upon a story about a hobbit (whatever that is—must keep reading!) and with the Brothers Grimm a story about a king and a queen; but Hemingway presents his characters to us effaced (the nameless “we,” “troops,” and “soldiers”) and the time and place in which they exist undefined. Didion calls this effect “the tension of withheld information.” The power of the opening paragraph of A Farewell to Arms, she notes, “offering as it does the illusion but not the fact of specificity, derives precisely from this kind of deliberate omission. In the late summer of what year? What river, what mountains, what troops?” Hemingway hooks us not with answers but with questions.

I recalled Didion’s reflections on A Farewell to Arms, and the deep textual understanding—and manifest joy—that they evince, when I came across an opinion piece in Slate last week by Adam Kotsko, a scholar of religion and political theology. “I have been teaching in small liberal arts colleges for over 15 years now,” Kotsko observes, “and in the past five years, it’s as though someone flipped a switch. For most of my career, I assigned around 30 pages of reading per class meeting as a baseline expectation. Now students are intimidated by anything over 10 pages. Considerable class time is taken up simply establishing what happened in a story or the basic steps of an argument—skills I used to be able to take for granted.” Kostko points to the “obvious culprits” behind this shift (“the ubiquitous smartphone,” “the massive disruption of school closures during COVID-19”) but also cites changes in K-12 educational practices. “The growing trend toward assigning students only the kind of short passages that can be included in a standardized test,” he writes, is tantamount to “actively preventing young people from developing the ability to follow extended narratives and arguments in the classroom.”

We are living—most of us reluctantly, I believe—in the Age of Abridgement. We give and receive the part as a substitute for the whole, or the summary as a substitute for the entirety. “It boils down to this,” we say. “Here’s all you need to know.” “Here’s the bottom line.” “Give me the highlights.” “Get to the point.” “I don’t have time for this.” “Yes or no?” We abbreviate when we should elaborate. We sample when we should immerse. We accept elevator speech for explanation, gist for understanding. We skim when we should read. This prevailing insistence on distillation inevitably infects our contemporary definition of education and our expectations of educational institutions, as Kotsko laments; and it should concern us at least a little when the leader of a university whose very name is a global byword for academic excellence is compelled to resign after defending—and being castigated for defending—the fundamental importance of context.

We are working hard to outlast the Age of Abridgement at MICDS, and we must work harder still. To be in a hurried world but not of a hurried world is easier said than done. At a great school the work begins with reading, and cultivating a joy of reading, across all disciplines. We must strive for understanding rather than settle for gist. Here’s how SparkNotes, the study-guide website whose oxymoronic tagline tells you exactly what you’ll be missing (“Studying, simplified”), summarizes those exquisite opening lines of A Farewell to Arms and several paragraphs that follow: “The narrator, Lieutenant Henry, describes the small Italian village in which he lives.” Well, yes—and no. Perhaps we should insist more often, “Don’t give me the highlights. Don’t get to the point. I do have time for this. Yes and no.”

I began this letter with Ernest Hemingway by way of Joan Didion. I will conclude it with Hemingway by way of Hemingway. “The writer’s job is to tell the truth,” he suggests in his memoir, A Moveable Feast. “I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, ‘Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence.’” Perhaps “one true sentence” can in fact be a summary and not an elaboration; but to “stand and look out over the roofs of Paris”? How can such an experience possibly be abbreviated, synthesized, boiled-down, bottom-lined, or highlighted? Hemingway knew that questions are more interesting than answers, and that good things take time. In our Age of Abridgement, we should know these things, too.

Always reason, always compassion, always courage. My best wishes to you for a restful and happy weekend. We will see you back at school on Monday.

Jay Rainey

Head of School

This week’s addition to the “Refrains for Rams” playlist: Tell Him by Lauryn Hill, the hidden track that concludes her debut and only studio record, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998), which is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest albums ever made (Apple Music / Spotify)