It isn’t often that you think of your kitchen and a chemistry lab as being one and the same. Experimenting with enzymes, bacteria, and molecular bonds sounds like the kind of research done in lab coats, not aprons, but students taking the Winter Term course Cooking from Scratch learned that science is a main ingredient in everything they eat.

The course was co-taught by Upper School Science Teachers Laura Bradford and Dr. Megumi Yoshioka-Tarver, known as Dr. Meg. Deciding to lead the course seemed like a natural decision. “We both love to cook” says Dr. Meg. Mrs. Bradford agreed, “We cook” but, ”we’re both science teachers and talking about the science behind it and the chemistry behind it is key.”

Dr. Meg and Mrs. Bradford led more than 30 students as they experimented with different recipes for bread, marshmallows, jam, yogurt, boba, and butter. “I’ve always been interested in cooking and baking but never had an in-depth knowledge of how some of the processes work” said Giacomo Castelmare ’25. “Before I thought, ‘You just put it the microwave or oven.’ Now I think there are a lot of intricacies to it.”

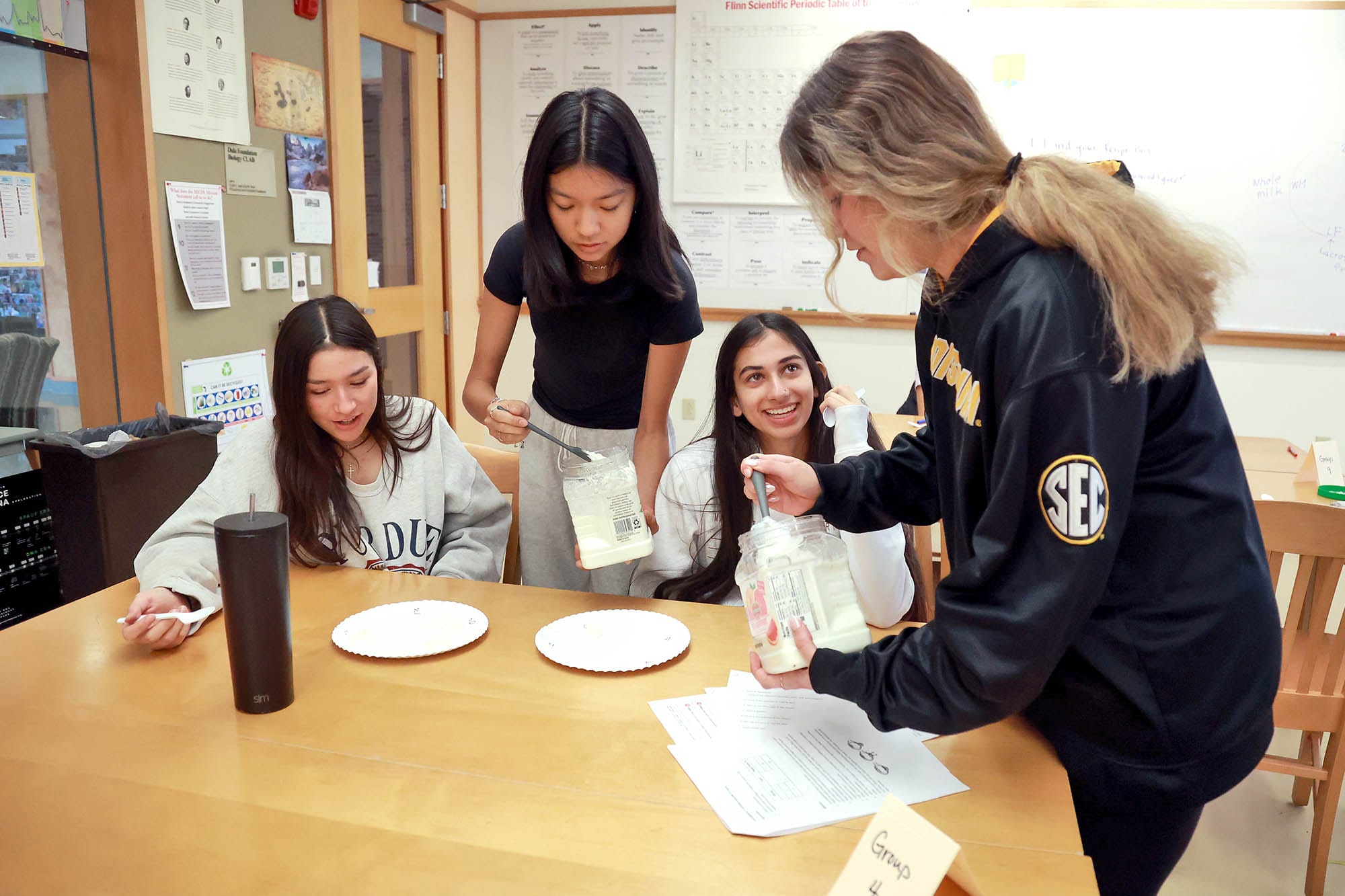

Some of those cooking intricacies included using milks with different fat and lactose contents to make yogurt. Students used whole (4%), 2%, skim (1%), non-fat (0%) milk, and lactose-free milk to make yogurt and then compared the results. The central question that day was, “How does yogurt work?” Mrs. Bradford explained that the bacteria eats lactose and turns it into lactic acid. Normal results were expected when using the milk and creams. When it came to the lactose-free milk, “we thought for sure it wasn’t going to do anything” said Mrs. Bradford. To the surprise of everyone, the lactose-free milk made some of the best yogurt, leading them all to ask, “how did lactose-free milk get digested by the bacteria?” Lactose is a disaccharide and people who are lactose intolerant don’t have the enzyme needed to digest it, but lactose-free milk is already “digested;” it has the disaccharide bond broken down into monosaccharide intermediates, glucose and galactose. Lactose-free milk became the best type to make yogurt because the bacteria didn’t have to go through the extra step of breaking the disaccharide bond; the monosaccharide food was already there. Mrs. Bradford and Dr. Meg were thrilled with the discovery. “It was a new finding!” said Dr. Meg.“We totally geeked out!” said Mrs. Bradford.

Similar experimentation with ingredients was performed while making marshmallows. Students tried different amounts of sugar and corn syrup – then tasted the results and picked the marshmallow they liked most.

For Dr. Meg the best part of the course was baking bread. She has been baking her own sourdough bread for years and said, “I was really happy that students got to experience the whole process.” Baking bread is an ideal way to incorporate science in to the kitchen. About bread, Dr. Meg emphasized, “It’s all about biology. It’s microbes. It’s a living culture that students have to take care of.”

That was certainly the takeaway for Garrett Liberman ’25. “I like baking and cooking in general, but I’ve never gotten in-depth into it. This class is interesting because we learned the chemistry of what yeast does in dough and went more intricate into the background.” Morgan Macam ’26 agrees. She cooks at home and enjoys her chemistry classes, “So I thought this class would be a good mix between the two” she said.

Narya Phatak ’26 found the class illuminating in several ways. “It’s really cool to get into the minds of how someone who invented these recipes would have figured it out” she said. “Using molecular gastronomy – how you have to use different sodium alginate and calcium chlorinate just to create a membrane around some juice for the popping boba – there’s a lot more that goes into it than people realize.” She continued, “Cooking is a very valuable life skill that I wanted to make sure I knew how to do. I definitely got that out of this class.”