Supporting students’ developing understanding of research and representation in art and history courses

By Dr. Sally Maxwell, Assistant Head of School for Teaching and Learning

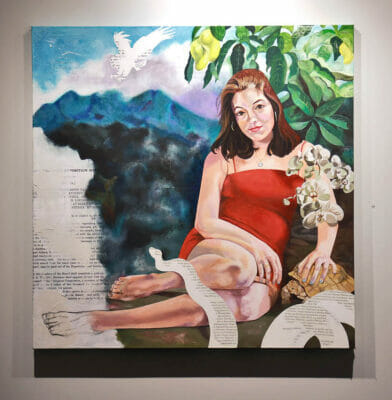

The first time I saw Ria Unson’s mixed media work, I was in a hurry, on my way down to the art department. As the Assistant Head for Teaching and Learning, my work is an interesting mix of future-oriented projects and unexpected challenges. So there I was, hurrying past and caught up in the business of school, and a painting grabbed me by the eyeballs. The painting was positioned to get attention—alone on a wall under three directional spotlights at the end of a long hallway. It’s dominated by a central image of a teenage girl in a red dress, barefoot and looking towards the viewer with one hand on a turtle. My eyes moved from her to take in the other elements of the painting: orchids, a bird, mangoes, mountains, and a snake. Then I noticed the technique. The snake’s body is made of text in a language I can’t read and the girl’s left foot extends into another (stripped away? unfinished?) section of text. The Messing Gallery, which Denise Douglas, Upper School Arts Teacher and Gallery Director, curates, is an essential space for student learning in our studio arts program because, as Douglas explains, “Having contemporary art in the gallery allows our students to experience what people are making artistically right now. It is a reflection of our society as it is.”

The first time I saw Ria Unson’s mixed media work, I was in a hurry, on my way down to the art department. As the Assistant Head for Teaching and Learning, my work is an interesting mix of future-oriented projects and unexpected challenges. So there I was, hurrying past and caught up in the business of school, and a painting grabbed me by the eyeballs. The painting was positioned to get attention—alone on a wall under three directional spotlights at the end of a long hallway. It’s dominated by a central image of a teenage girl in a red dress, barefoot and looking towards the viewer with one hand on a turtle. My eyes moved from her to take in the other elements of the painting: orchids, a bird, mangoes, mountains, and a snake. Then I noticed the technique. The snake’s body is made of text in a language I can’t read and the girl’s left foot extends into another (stripped away? unfinished?) section of text. The Messing Gallery, which Denise Douglas, Upper School Arts Teacher and Gallery Director, curates, is an essential space for student learning in our studio arts program because, as Douglas explains, “Having contemporary art in the gallery allows our students to experience what people are making artistically right now. It is a reflection of our society as it is.”

Dr. Kevin Slivka, Upper School Art Teacher, talked with me about how his art and Unson’s both focus on art as postcolonial reconciliation. Dr. Slivka’s work, which is also multimedia, is an attempt to cast a new relationship between previous European artists and the first Americans. He worked with Indigenous printmakers on maps and locations of burial sites. Like Unson, research is part of his artistic process and connected to his identity. Dr. Slivka explained, “In identifying as a white, middle-aged, heterosexual male who can travel into many spaces without having any issue, I have to decenter myself to enter indigenous land.” He sees Unson’s work as an opportunity to help students understand how artists “use artistic practices to communicate complicated ideas.” Dr. Slivka showed me one of his pieces that uses macrame and painting on untreated canvases to explore the restriction of Ojibwe fishing rights by the U.S. Department of Natural Resources. To coincide with Unson’s exhibit, Dr. Slivka asked her to share a gallery talk with his 2D painting class. We got together on a Friday morning in Messing Gallery. Unson captured our attention right away as she began, “My great-grandfather…”

Teaching our developing artists how identity and history inform artistic practice

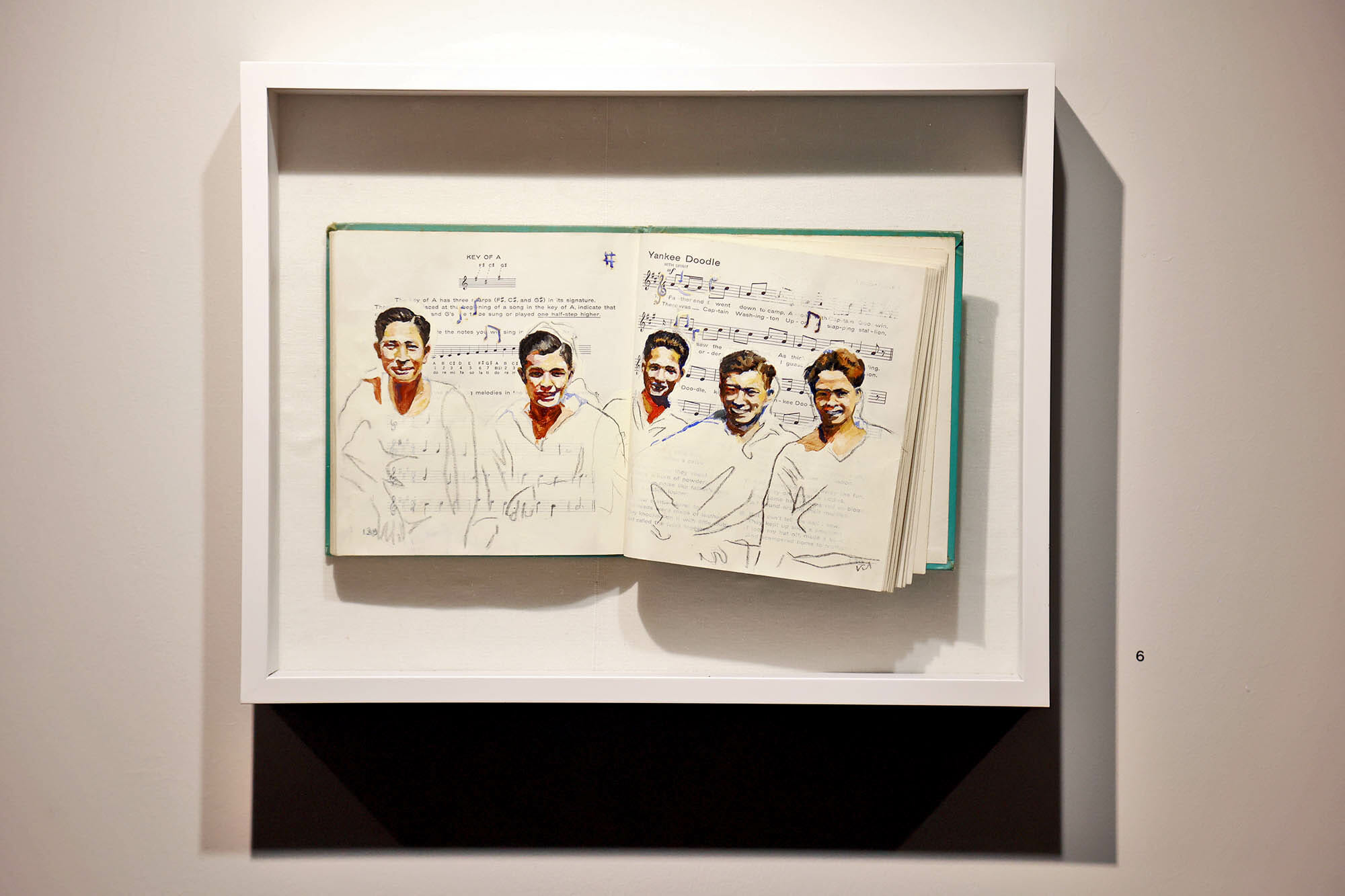

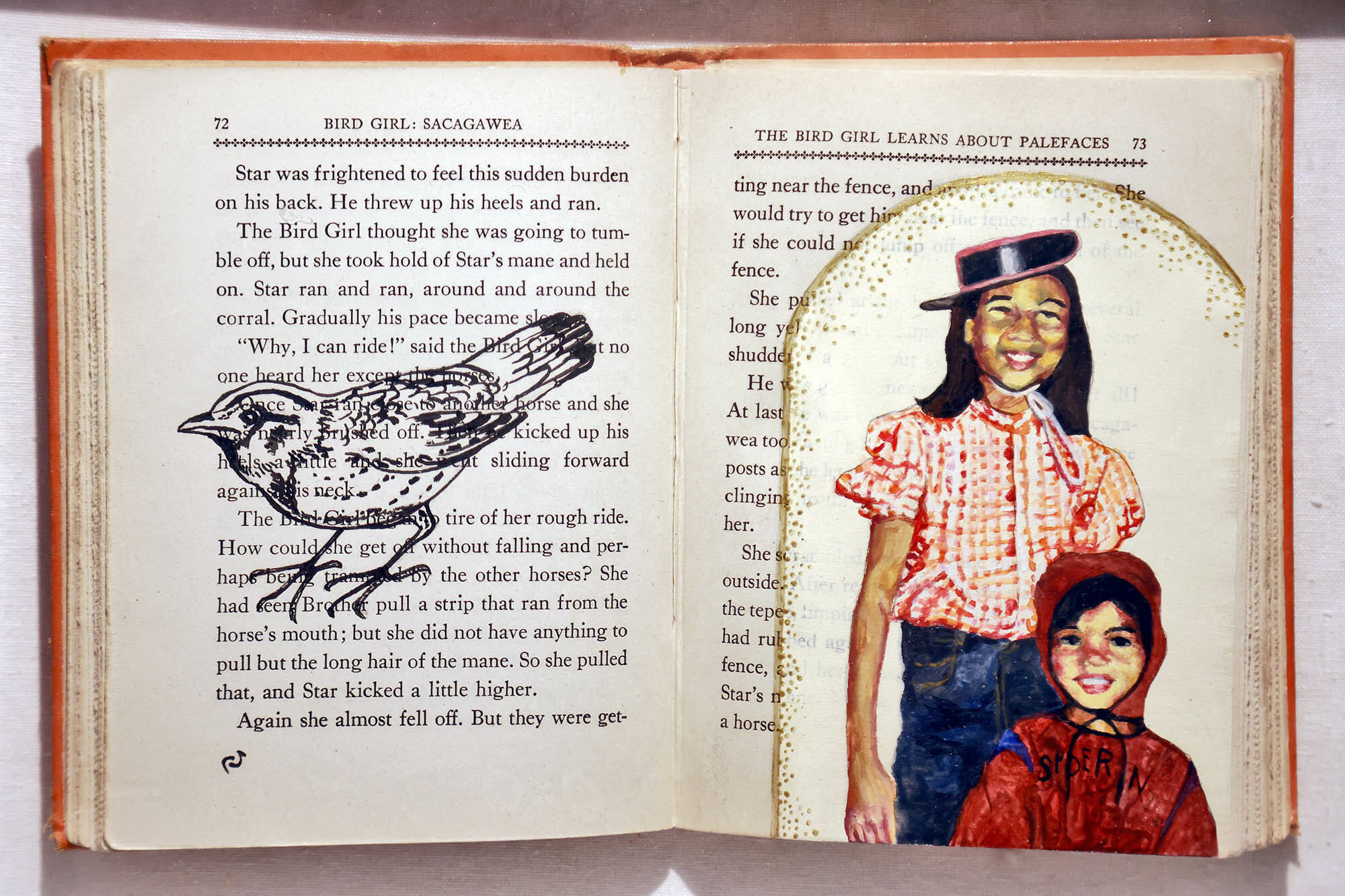

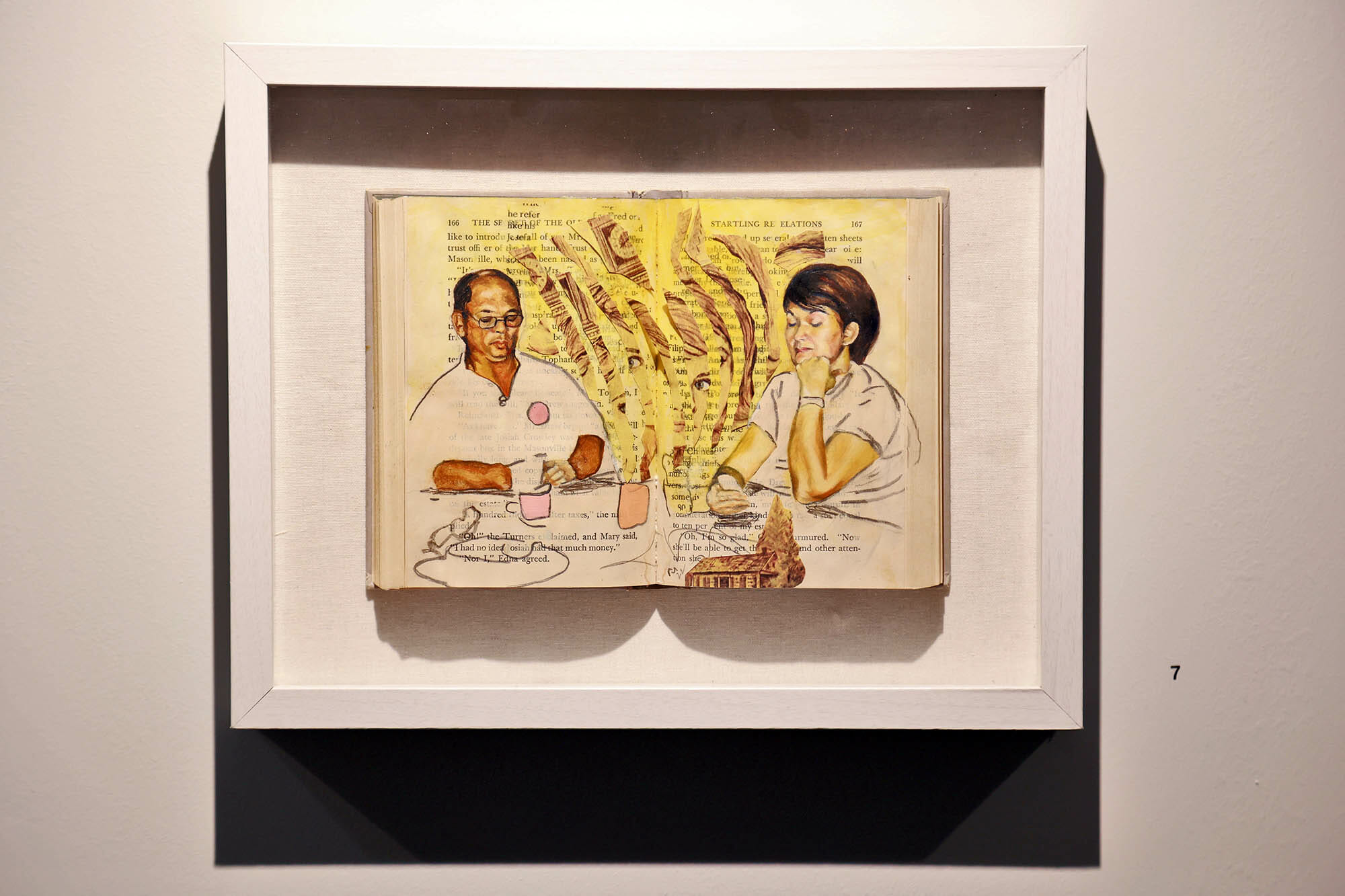

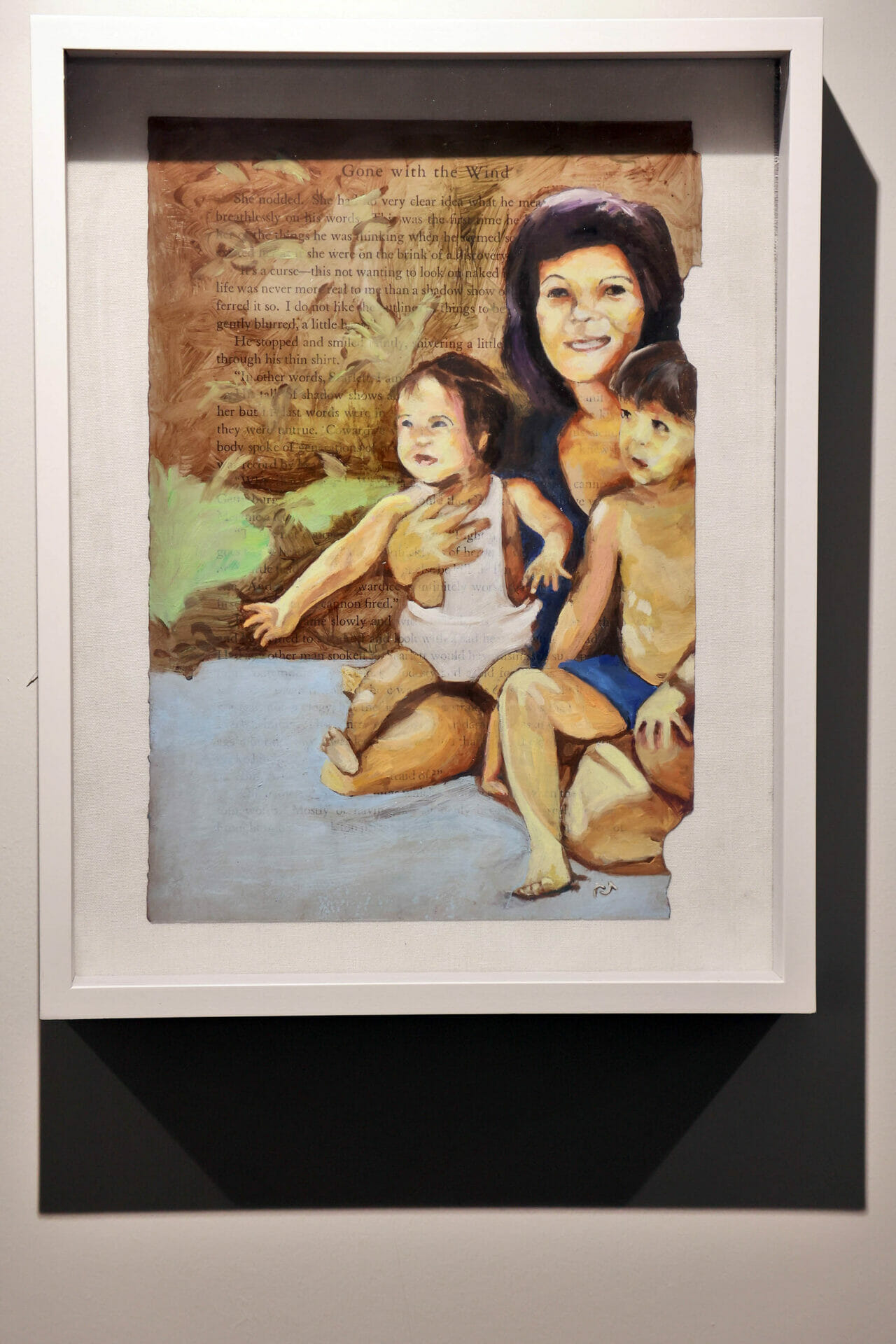

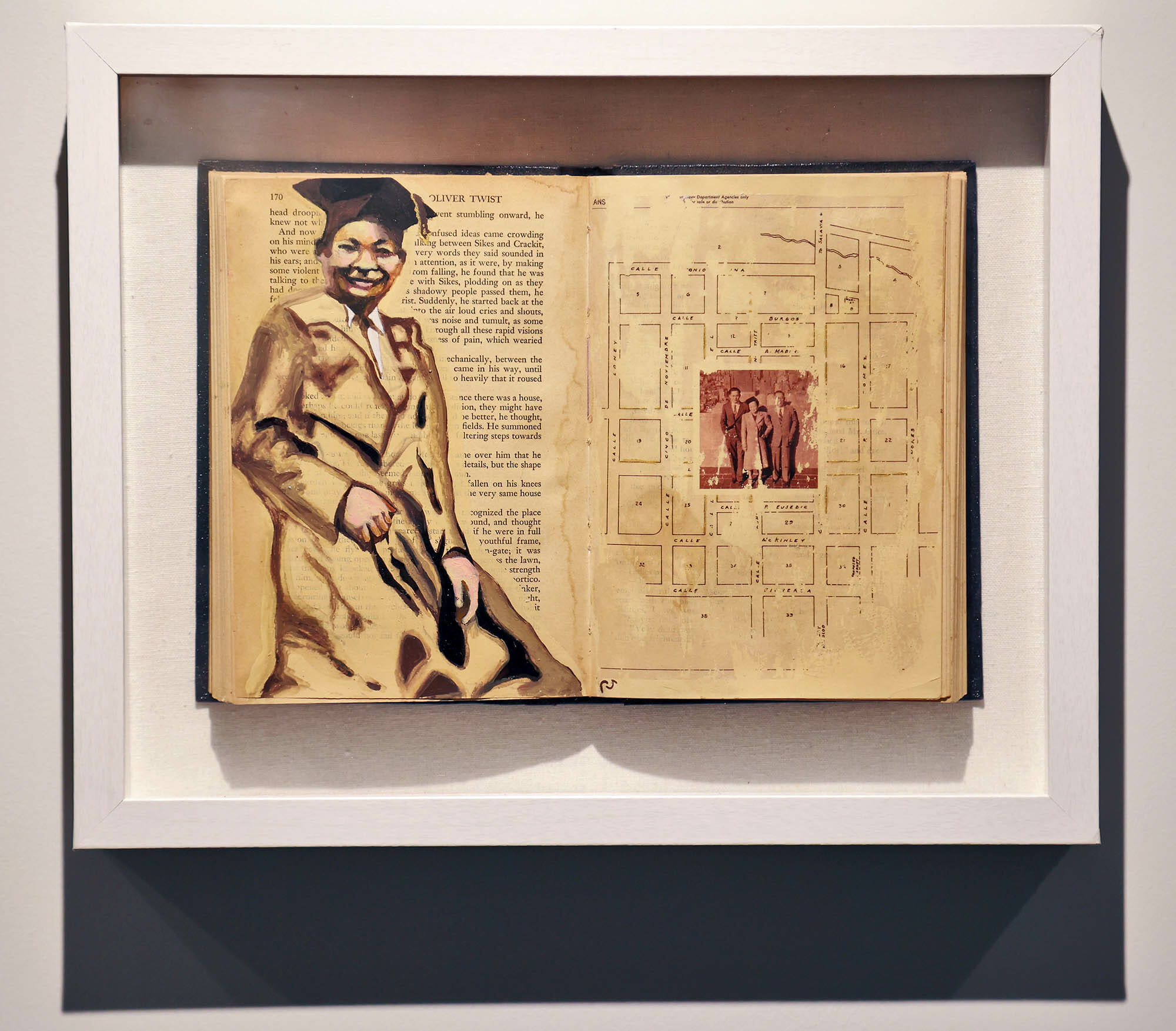

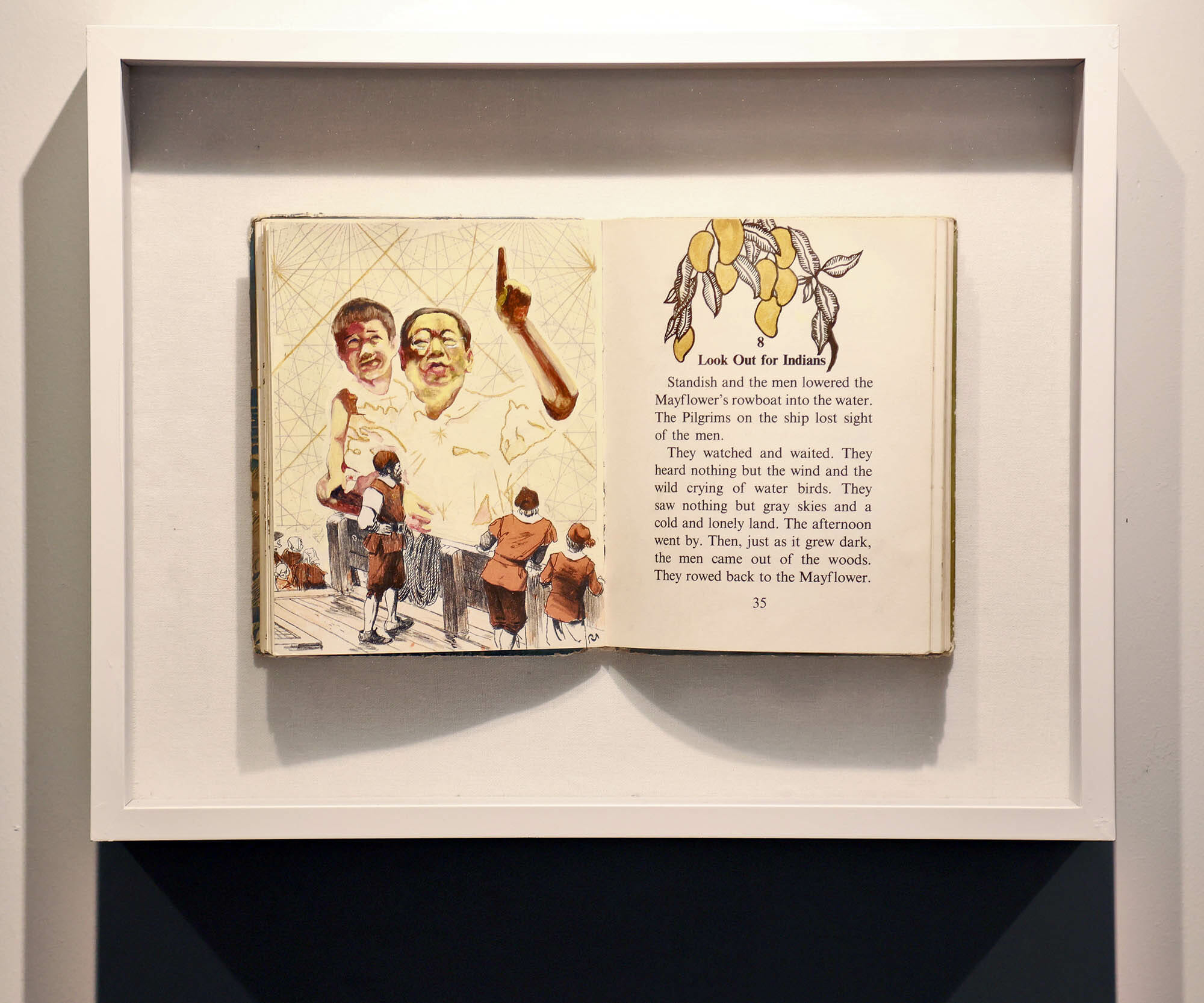

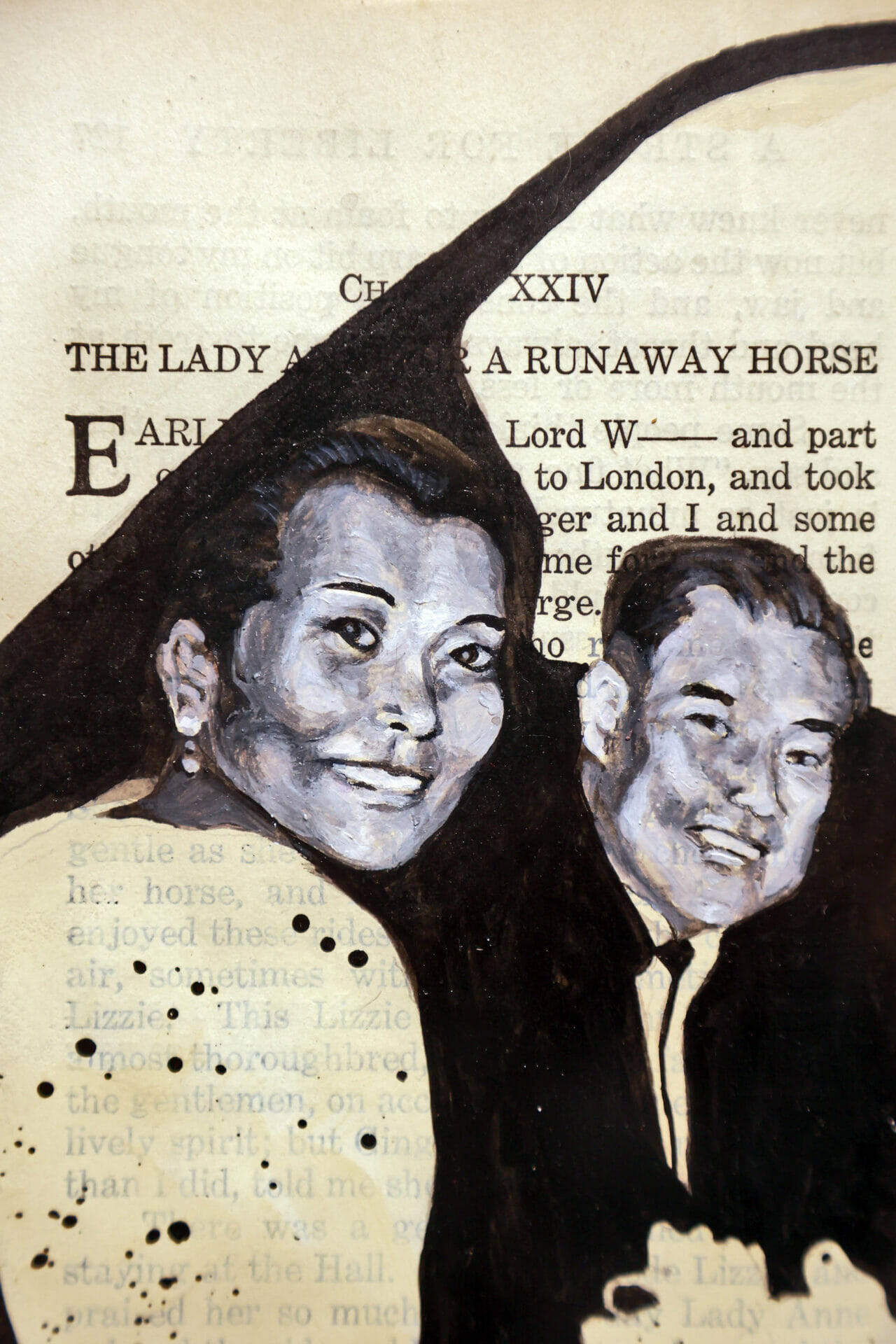

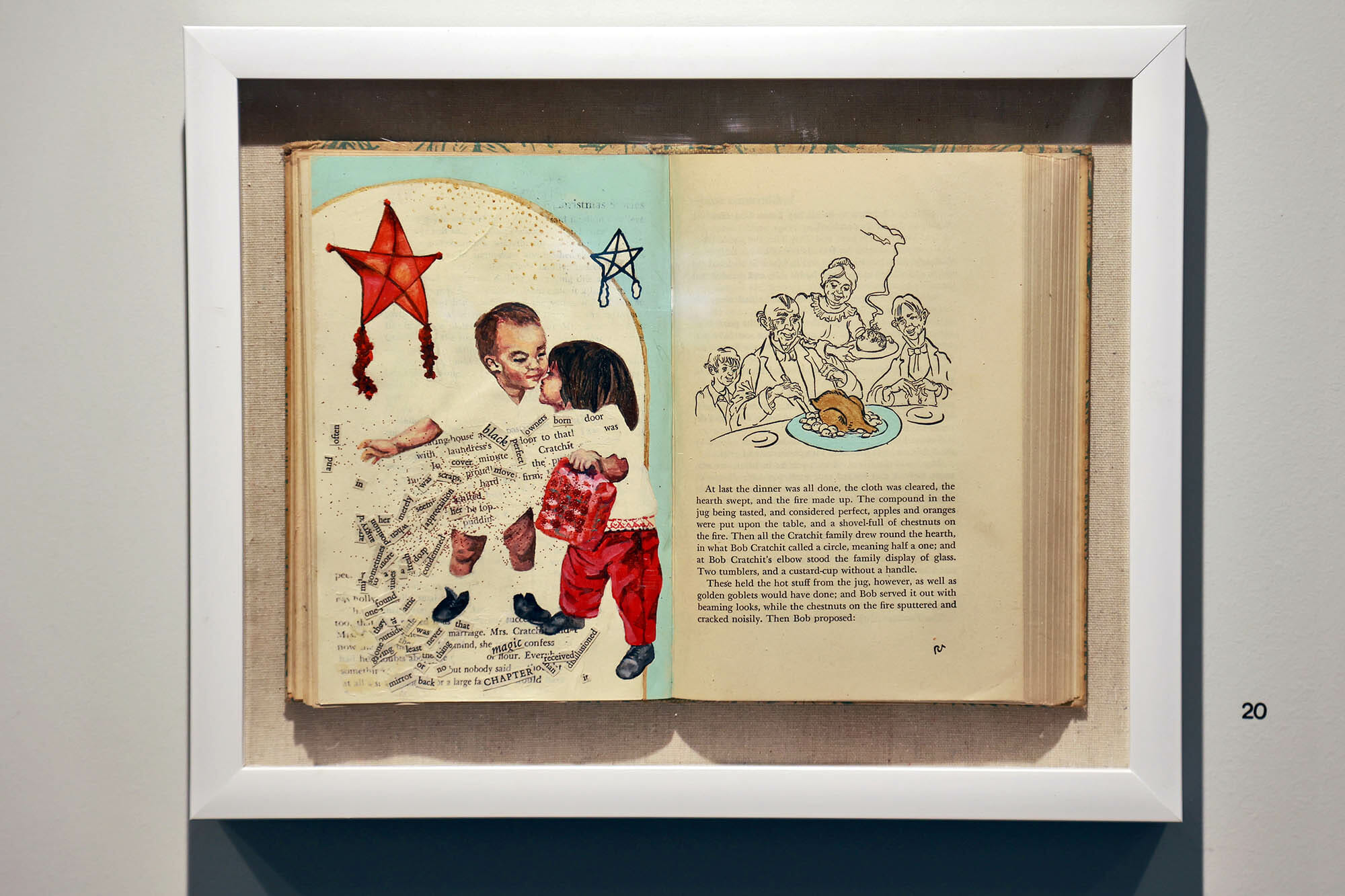

Unson’s great-grandfather was brought to St. Louis in 1904 as part of a group of Filipino students who were given scholarships to attend American universities and worked at the fair before they went to their designated colleges. They toured visitors through the constructed wooden huts to embody the idea that America could colonize the Philippines and turn primitives into Westernized people who could speak perfect English. He returned to the Philippines after his American education and became a captain in the Philippine Constabulary, a paramilitary force established by the American military to help suppress Filipino insurgents. Unson had a very Westernized childhood in Manila, eating McDonald’s and speaking English at home. At 13, she followed the path of many of her family members and went to the U.S. for school. As a teenager landing in Madison, Wisconsin, Unson was taken aback when classmates asked her if she ate dogs. In her research as an adult and artist trying to make meaning from her own life, Unson learned that the stereotype that Filipino people ate dogs was popularized at the World’s Fair and published in newspapers at the time. She shares with Slivka’s students, “As a Filipino, you never see yourselves on walls in art galleries. I feel a responsibility as someone with a marginalized identity to flood the archive with images. The archive is never neutral.” For Unson, research is part of the process and is visibly reflected in her work. She layers text and images. She adds portraits of her own family members to book illustrations. Dr. Slivka asks Unson if she is seeking a resolution or if the tension in her work is perpetual. She answers, “It’s always unresolved.”

Unson walks the painting class to the same piece that had absorbed me and explains that it is a portrait of her daughter layered with a World’s Fair document and the myth of Maryang Makiling. Maria was a Filipino woman with two suitors—a foreign soldier and a local Filipino man. The soldier had his rival killed and Maria cursed him. Unson included mangoes because the word for mango is a sexualized term for a Filipino woman. William Howard Taft once said, “Your islands are as beautiful as your women.” The painting represents Unson’s identity extending to the past and to the future of her family and the Filipino people. The daughter is a physical person who lives in two worlds. Unson is interested in how the colonized see themselves. She says, “They see themselves through a lens. There was always empire—before the Americans, the Spanish, and before that, the Javanese. How do you not be a victim? How do you reclaim these narratives and make them something positive?”

Alex McCarter ’25 found the gallery tour interesting. He said, “My mom is from Vietnam, and she was also colonized.” Alyssa Harris ’25 thought that Unson’s message was “how important it is to find your voice when people before you have been shut down…reclaiming our stories but telling them in our own way to resist assimilation.”

Helping our developing historians see art as both artifact and research

When the History Department learned about Unson’s exhibit on campus, they also jumped on the opportunity to gather the History of St. Louis class for a special presentation. The course’s curriculum includes the World’s Fair and its Philippine Exposition. Alex Rolnick, Upper School History Teacher, explained the value of the connection since “Ria’s focus on careful observation and her invitation of students to notice and ’dig a little deeper’ into the ideas and beliefs they have” hews so closely to the MICDS mission of building our students’ critical thinking skills.

We gather together after lunch in Brauer Auditorium. Students come in chatting and checking their phones. Chris Ludbrook, Upper School Dean, calls out, “All right, Juniors, zoom on down. Get ready!” A student asks me whether they have to take notes. Unson begins, “I hear that you guys are studying the World’s Fair.” She clicks through slides of photographs of the fair and shows students how it was organized to create a striking contrast between the huts of the Philippine Exhibition and the grand vistas of the Western buildings, willfully ignoring that Manila was, even at that time, a thriving cosmopolitan city. She shares the work of historians who connect the fair to then Governor General of the Philippines William Howard Taft’s goals of building support for colonization. The Philippine-American War (“Have you heard of that?” Unson asks. Students nod.) began when America took possession of the Philippines from Spain at the end of the Spanish-American War. It led to the death of one million Filipino people. Taft hoped the fair would bolster support for the ongoing occupation of the Philippines and “exert a very great influence on completing the pacification” of the Filipino people. Unson stands before the students, an American, and also the intended object of Taft’s plan. But she commands the room and tells the story.

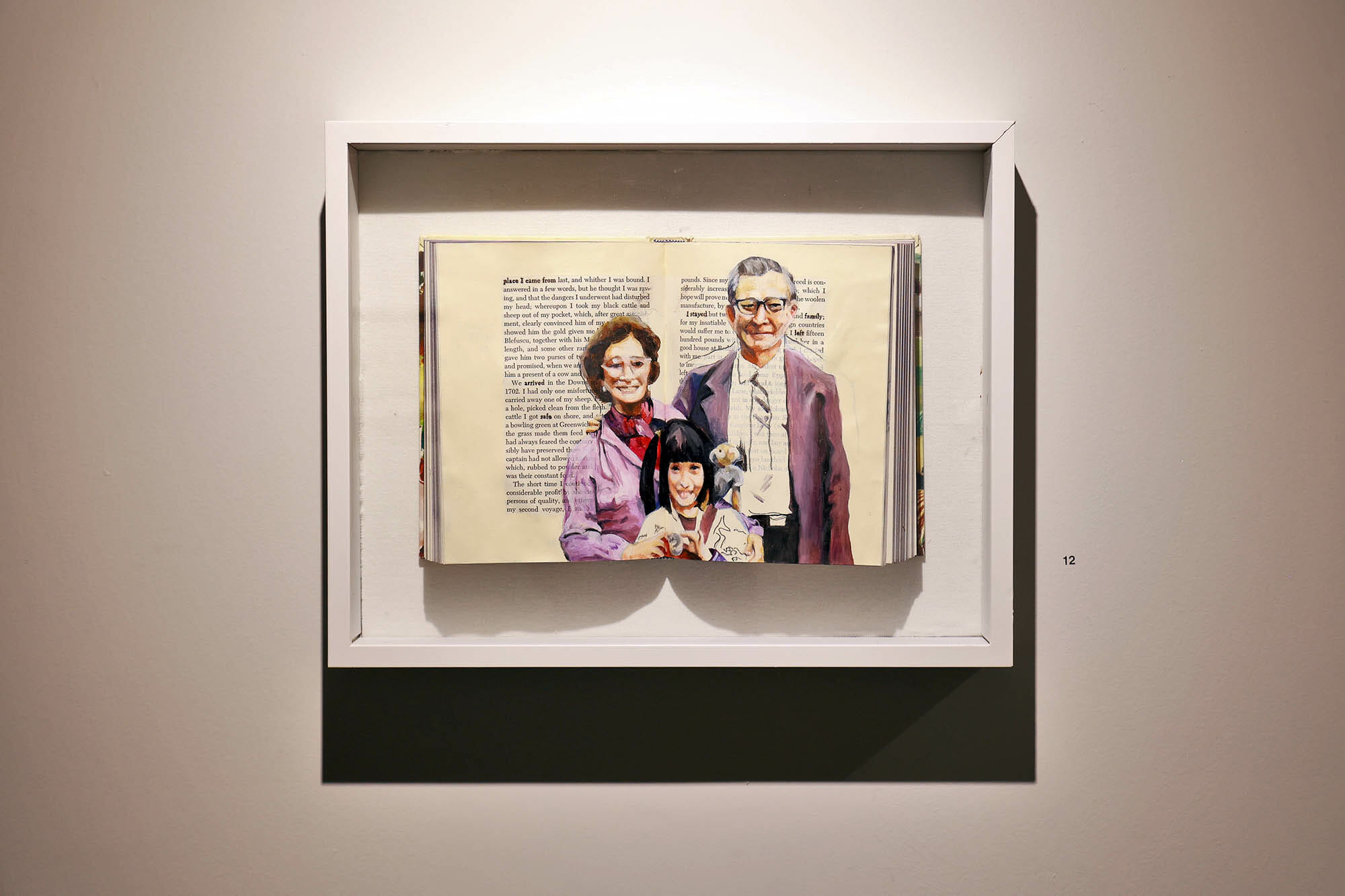

She wraps up her presentation by asserting that students need to understand that what they see must be read for its intentions. “Who is the work by, and who is it for?” With the Philippine Exposition, Taft was very explicit about his goals to implant ideas with Americans that served his goals. Because for American fairgoers in 1904, Unson argues, there was some cognitive dissonance between a narrative of liberation and the ongoing occupation and colonization of another country. In a democracy, politicians are always trying to bolster their support. And those same tools of representation are available to all of us. Since America colonized through stories and education, Unson uses books in her work. She painted a portrait of herself and her grandparents on top of a page from Gulliver’s Travels. Unson ends her talk: “Ideas that you hear may serve someone else’s agenda. And not just humans—now bots.”

The day after the talk, I am in JK-12 History and Social Sciences Department Chair Carla Federman’s History of St. Louis class in the library as she asks students to share what struck them from Unson’s talk. Anika Mulkanoor ’25 says, “I thought it was interesting that people make assumptions and have stereotypes of different places. Manila is similar to New York.” Mulkanoor talks about stigmas and how they can interfere with people’s understanding of where there are opportunities. The conversation then turns to the papers they are all working on in different classes as I slip out of the back of the classroom.

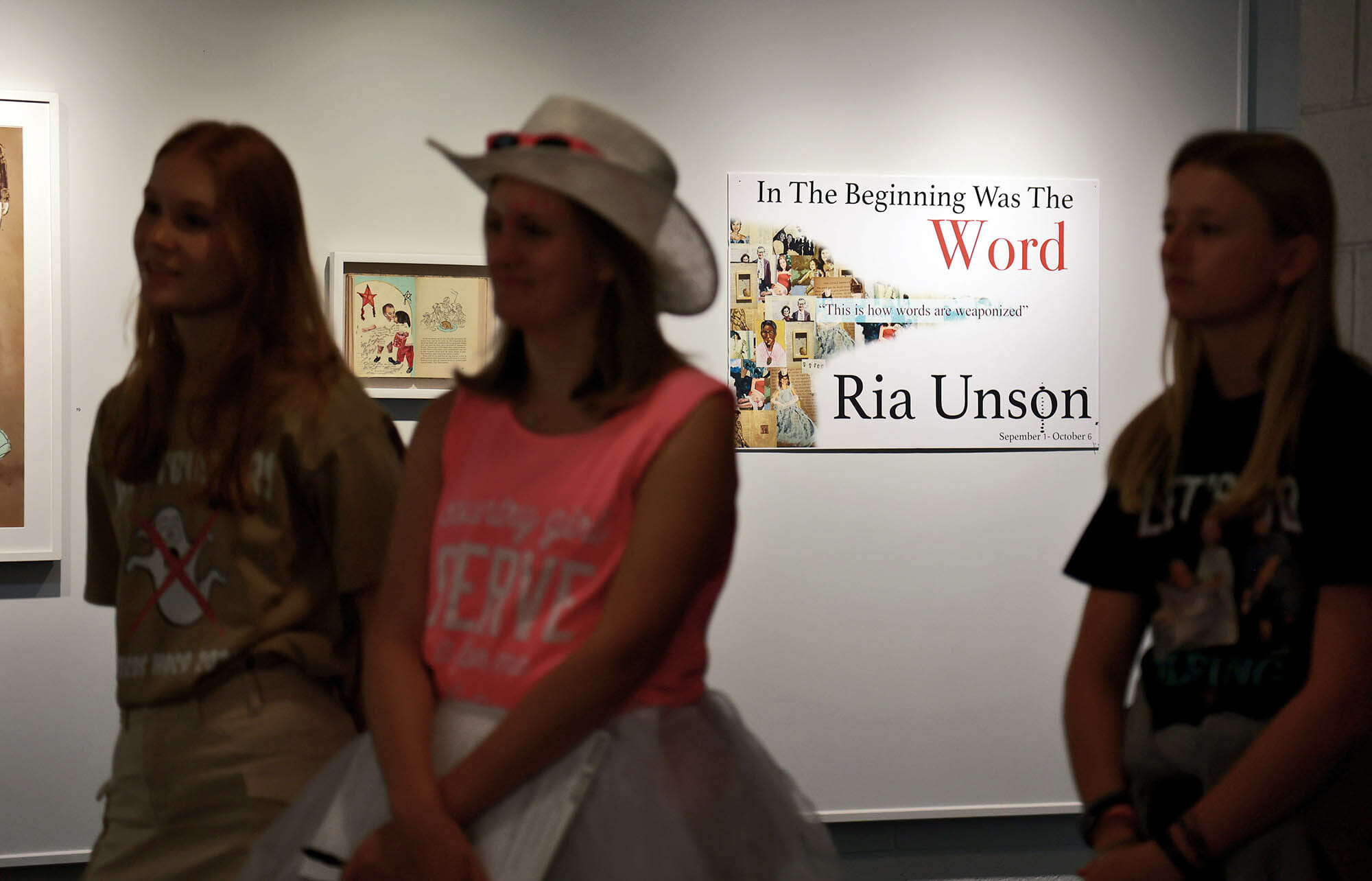

Ria Unson: In the Beginning Was the Word was on exhibit in the Messing Gallery, a gift of the Messing family, in memory of Roswell Messing Jr., class of 1934. Did you miss the exhibit? Visit Ria Unson’s website.