In a recent episode of the podcast series Conversations with Tyler that was recommended to me by an MICDS graduate and parent—and which I highly recommend to you in turn—the writer David Brooks recalled to host Tyler Cowen a visit to OpenAI’s headquarters several months ago. “Somebody said, ‘We’re going to create a machine that can think like a human brain.’ And so I call my neuroscientist friends, and they say, ‘Well, that’ll be a neat trick, because we don’t know how human brains think.’”

“One human being can be a complete enigma to another,” wrote Ludwig Wittgenstein in Philosophical Investigations. “We learn this when we come into a strange country with entirely strange traditions, even given a mastery of the country’s language. We do not understand the people. We cannot find our feet with them.” I love the way that Wittgenstein put things. “Cannot find our feet.” Can we ever find our feet with anyone? Sometimes we cannot find our feet with ourselves. Mind is mystery. “If a lion could talk,” Wittgenstein added, sticking the landing, “we could not understand him.” He certainly would not speak in binary code. Isn’t “machine language” an oxymoron? When did we stop knowing that it was?

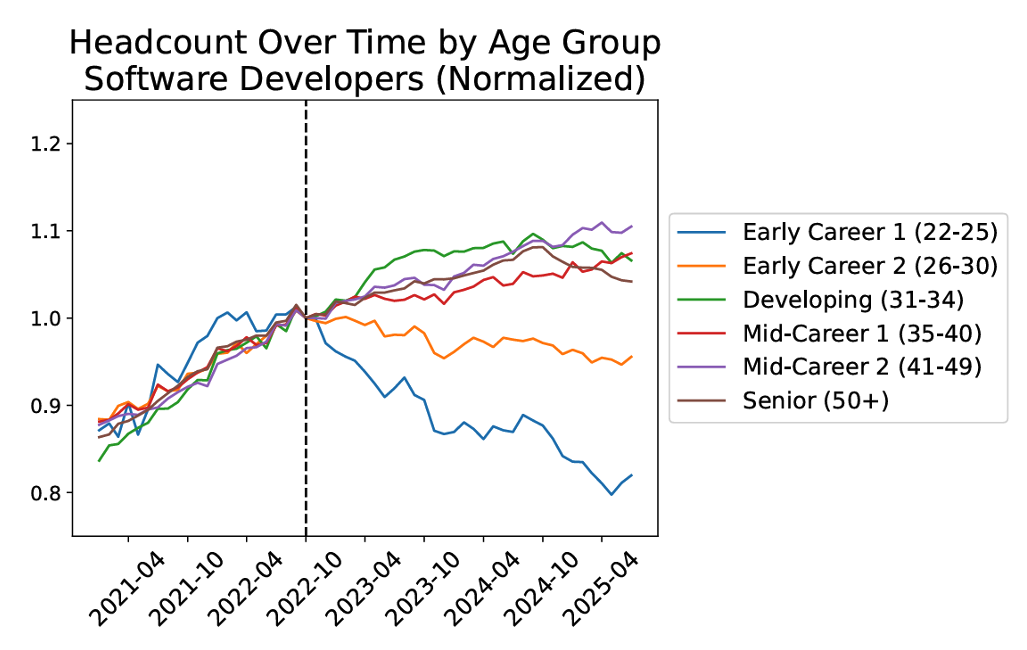

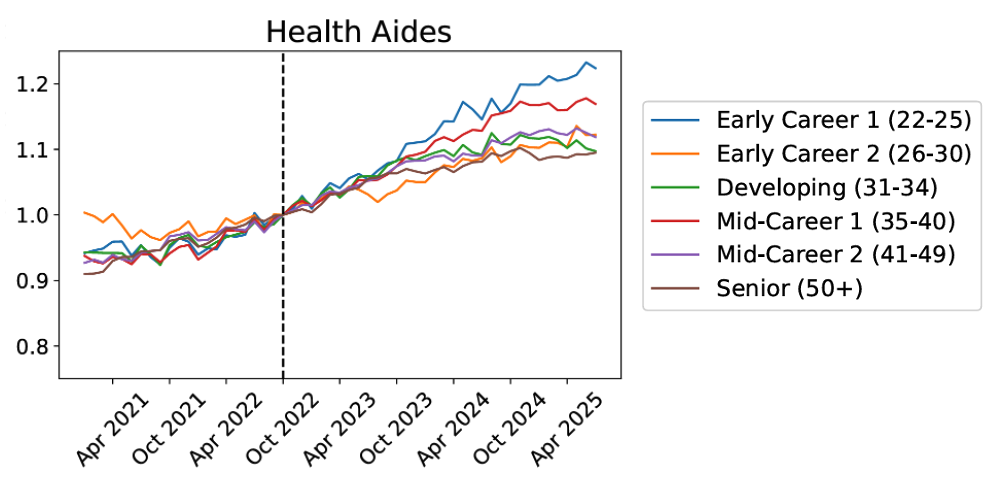

It’s been over 10 years since Yale professor David Bromwich declared “people being replaced by machines” as “the great social calamity of our time.” Certainly the advent of large language model artificial intelligence supports his claim, but only up to a point. Impacts are uneven. Last week, three Stanford labor market researchers—Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen—shared their finding that “entry-level employment has declined in applications of AI that automate work, with muted effects for those that augment it.” Job prospects for young software developers are rapidly diminishing, for instance, whereas the opposite is true for nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides. (The latter revelation should surprise exactly no one. A Google search for the phrase “AI to enhance patient care” turns up 222,000 hits. A search for “AI to automate patient care” turns up only 4, thank goodness. Isn’t “automatic doctor” also an oxymoron? May we never stop knowing that it is.)

A year ago, social scientists in Singapore analyzed data from 63 countries from 2005 to 2021 and concluded that industrial robot utilization—contrary to conventional wisdom—increased rather than reduced overall employment. Job opportunities evolved, but they did not disappear. I expect we will find the same to be true with AI, and that Bromwich’s “great social calamity” will transpire—is indeed already transpiring—not so much in the workplace as in the town square, the school, the neighborhood, the home, the relationship, even the individual self-conception. Notwithstanding the hubris of the good folks at OpenAI, far higher than the probability that AI can be trained to think like a human being is the probability that human beings can be trained to think like AI and still call it thinking.” Sam Altman’s misanthropy is not entirely unwarranted.

Our fascination with machine learning (also an oxymoron?) is the apotheosis of what the journalist Nicholas Carr dubbed “the shallows” back in 2011. Do we no longer fascinate ourselves? “What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals!” Where have you gone, William Shakespeare? (As I quote him here, an AI is suggesting improvements to his prose.)

“I think AI is a great tool,” David Brooks told Tyler Cowen, “but I’m unthreatened by it because I don’t think it has understanding, I don’t think it has judgment, I don’t think it has emotion, I don’t think it has motivation. I don’t think it has most of the stuff that the human mind has. It’ll teach us what we’re good at by reminding us what it can’t do.” Among the things that “we’re good at,” according to Brooks—or that we should try to be good at again—is audacity.

It seems to me there has been a loss of audacity in the culture, and it’s been replaced by professionalism and commercialism. The great high points of Western art are defined by audacity. You look at the Renaissance — that was audacious. You look at the Russian novels — that was audacious. I think we’re just not at a moment where that kind of self-confidence — which is very hard to manufacture for one person; it takes a whole group — I just think we’re not at that moment. I think [audacity has] left the humanities. I think the humanities have been backfooted, in part because, again, the internet, all that stuff, the obvious stuff. The reason you would go to become an English major was because you want to understand how human beings operate. You want to be able to see the world.

What might audacity look like in the face of the apotheosis of the machine? In the face of AI, it might look like an insistence on originality. “Trust thyself,” urged Ralph Waldo Emerson. “Every heart vibrates to that iron string.” No AI would have ever “known” to play the guitar like Jimi Hendrix knew to play it—and where would humanity be without Jimi Hendrix? (If Jimi Hendrix’s Stratocaster could talk, we could not understand it.) In the face of social media, audacity might look like the courage to stand up for a friend, or a stranger—a refusal to “cancel” anyone.

In the face of technoconsumerism, audacity might look like self-actualization through self-denial, a willingness to buy less, to conform less, to swipe less, to scroll less. In the face of professionalism and commercialism, it might look like believing you can major in English and still have a career. (When did we stop knowing that sociology is harder than engineering?) In the face of political dysfunction, audacity might look like humanizing someone with a different perspective than your own. “Our core problems,” Brooks said to Cowen, “are sociological and cultural and psychological and moral. If you wanted to work on a core problem, rebuilding social trust — if you can figure out how to do that, it would be an awesome contribution.”

“If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.” Maybe so, but wouldn’t you—the paragon of animals—want the audacity to listen anyway, to find your feet in that strange country, to be alive to the unknown and the unknowable, the unalgorithmable and uncommoditizable? We want nothing less than such constructive audacity (not an oxymoron!) for our students at MICDS, and we will continue to seek it with them with hearts full of curiosity and hope for the future.

Always reason, always compassion, always courage. My best wishes to you for a happy weekend ahead.

Jay Rainey

Head of School

This week’s addition to the “Refrains for Rams” playlist is Castles Made of Sand by Jimi Hendrix (Apple Music / Spotify).