This week, Upper School students gathered in Brauer Auditorium for the annual Harbison Lecture.

The Harbison Lecture is named in honor of Mr. Earle H. and Mrs. Suzanne Siegel Harbison ’45. In 1994, Mr. and Mrs. Harbison established the Harbison Lecture Fund to commemorate Mrs. Harbison’s 50th Class Reunion. Its purpose is “to fund an annual lecture for students at MICDS featuring a prominent local, regional, or national figure whose topic will support the mission and educational goals of the School.” Since the Harbison family strongly values the sciences, MICDS has historically chosen a leading figure in the sciences to speak. For the 2025 Harbison Lecture, the Upper School at MICDS was delighted to welcome Dr. Kristina Dahl, a scientific leader in the climate research and communication space, who joined the assembly virtually via Zoom. After a short welcome, Paul Zahller, JK-12 Science Department Chair & Upper School Science Teacher, turned the mic over to Siboney Oviedo-Gray ’26 to introduce Dr. Dahl. Her remarks are below.

Kristina Dahl, Ph.D., is the vice president for science at Climate Central. In this role, she leads Climate Central’s scientific activities and helps design analyses that enable people across the world to connect their lived experiences to climate change. Over the course of her career, Dr. Dahl has researched a range of different climate impacts, from the effects of extreme heat on outdoor workers to the connection between heat-trapping emissions and worsening wildfires.

Prior to joining Climate Central, she served as a principal climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, where her work supported the development of climate-aware public policy at the local, state, and federal levels.

In 2023, she was named a TIME100 Next Innovator. Dr. Dahl holds a B.A. in earth sciences from Boston University and a Ph.D. in paleoclimate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program. She has extensive experience working with print, radio, and broadcast TV reporters and communicating about a wide range of climate-related issues. She has been interviewed and quoted by prominent outlets, including The New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, PBS NewsHour, NPR, USA Today, and People.

The program began with several student and faculty moderators asking Dr. Dahl questions based on specific topics, including heat stress and human health, flooding and community vulnerability, climate change and adaptation, and science and society.

Heat Stress & Human Health

“Schools and curricula can do more to address climate change. Growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, climate change wasn’t discussed in school, but things have shifted; my kids have touched on it every year since fourth or fifth grade. To create a safer climate, your generation needs to understand the role of misinformation and disinformation, including how to spot it, combat it, and ensure accuracy in social media sharing. It’s also crucial to comprehend the scientific process and the current understanding of climate change. Studies show 97% of scientists agree that climate change is occurring and that human activities are a contributing factor. However, public polls reveal a discrepancy: the general public, while mostly believing it’s happening, doesn’t align with the scientific community’s consensus. Schools can help build a case for climate action by discussing how scientific consensus forms and what that term truly means.

”St. Louis, like most U.S. cities, has an urban heat island effect, meaning it’s generally hotter than its surrounding areas. This is because urban environments have a high concentration of man-made materials that absorb and radiate heat, unlike natural landscapes with green spaces and trees. Cities can combat this by redesigning urban areas. Even within a city, areas with more shady trees or park space tend to be cooler. Also, the hotter versus cooler parts of a city often fall along racial and socioeconomic lines. Moreover, some cities were historically not built to be inhabitable, frequently resulting in lower-income neighborhoods and higher populations of Black and Brown people experiencing the worst heat. Change requires looking across the entire city to identify and assist the communities most in need.”

Flooding & Community Vulnerability

“When heavy rain falls, flooding occurs due to two main factors. First is the land’s surface. A natural area, like a meadow with grasses and roots, acts like a sponge, allowing water to percolate into the soil without causing floods. Conversely, a paved-over landscape with lots of concrete leaves nowhere for the water to soak in, forcing it into basements and houses. The second factor is the rate of rainfall. The ground can absorb five inches of rain over five days, but five inches in a single event is too much water to absorb at once, leading to flooding. Your region has recently experienced this. It’s likely a combination of the land surface being more built up and, with climate change, a trend toward more extreme, heavy rainfall events.”

Extreme heat is often called the silent killer because it receives less attention than events like wildfires or hurricanes, yet it kills more people in the U.S. annually than any other type of extreme weather. Exposure to extreme heat causes a range of health issues, from nuisances like headaches and dizziness to potentially fatal heat stroke if core body temperature rises too high. It’s crucial to be aware of the symptoms of heat-related illness.

When it comes to children, their bodies don’t process heat as effectively as those of adults, and they are often less aware of their physical state while being active, making them more susceptible to heat-related problems.

Beyond health, heat affects learning. Studies of high school students in New York state found that as classroom temperatures rose during standardized testing, scores went down. It is simply harder to learn and perform well on tests when it’s hot. If the scores on high-stakes tests are impacted, this can have lifetime repercussions for college admissions and future opportunities, simply because the testing environment was too hot.

“There’s also a recreational aspect to this. I grew up in the Midwest running around outside all summer, but in my hometown of Pittsburgh, it’s now often too hot for kids to play outdoors. Extreme heat is changing what childhood looks like. Of course, this dovetails with other societal trends, like more families having two working parents, meaning less unsupervised outdoor time, and the rise of video games. So, while extreme heat isn’t the only factor, it is playing into these changes that point to a childhood spent less outdoors and with less exploring.”

Climate Change & Adaptation

“Climate models predict significant increases in both extreme heat and extreme rainfall for St. Louis between now and the middle of the century. Regarding extreme heat, we expect to see about a doubling in the number of days above 90 degrees within your lifetime. For extreme rainfall and flooding, a warmer atmosphere acts like a sponge. It sucks moisture from soils, potentially causing more droughts, but it also holds more water that can be released as extreme rainfall. The Midwest has already seen a clear trend of increased heavy rainfall events, and as the planet continues to warm, the air will hold even more moisture. We expect the frequency of really heavy rainfall events to increase further, requiring communities to prepare now to mitigate flooding risks.

“To prepare for increased flooding, we need to consider things like moving people out of very flood-prone areas. This requires taking a hard look at who is living in the most flood-prone areas and why. Often, the properties most at risk of flooding have historically been the most affordable. People who lack intergenerational wealth, those who may never have been property owners before, or those who have been discriminated against or left behind by government systems, are frequently the ones living in these high-risk zones. Therefore, ensuring we have programs that can help all people adapt and become more resilient to floods will be truly key as we look toward a future where flooding is likely to become more frequent.”

Science & Society

“Some of the most gratifying work I’ve done recently involves heat protection standards for outdoor workers. While the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has numerous federal rules in place for safety, such as requiring the provision of hard hats at construction sites or protecting against toxic fumes, there is currently no federal rule that specifically protects people who work outdoors from extreme heat. There’s no federal standard defining a temperature at which it’s simply too hot for workers.

“Consequently, individual states have started passing their own laws. California, for example, has had rules on the books since 2006, enacted after a major heat wave where many outdoor workers lost their lives. Much of the science on extreme heat focuses on how many hours per day are safe for physical work as global warming raises temperatures. States like Oregon, Washington, and Maryland now have heat protection rules in place, and others are exploring similar measures. Since federal movement on this issue through OSHA has largely stalled, state-level action remains crucial to protect these vulnerable workers.”

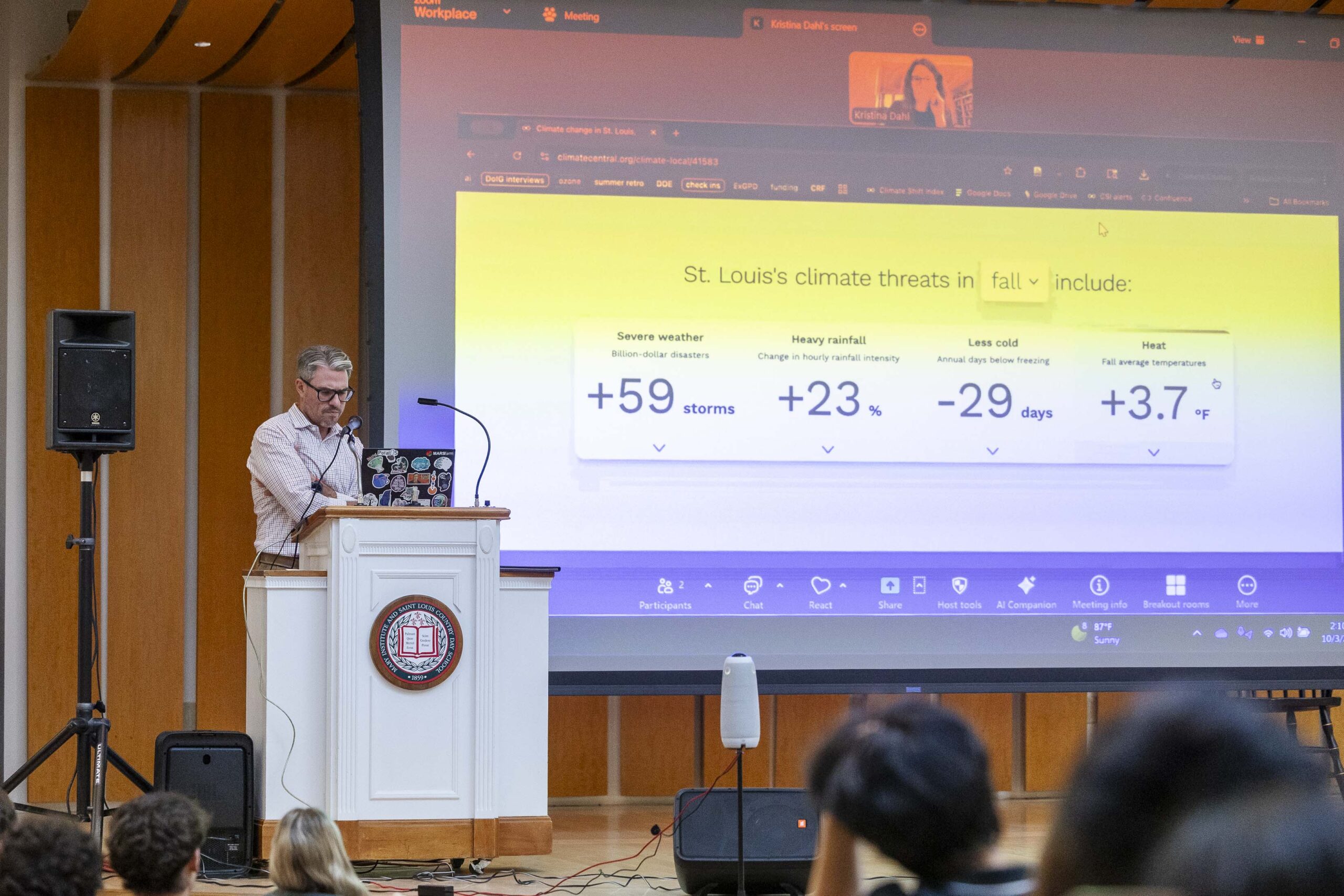

Dr. Dahl then demonstrated the “Explore Your Climate Story” dashboard on ClimateCentral.org, which offers climate data specific to St. Louis and other areas worldwide.

She highlighted several key local impacts, such as an increase in annual precipitation rates since 1970, a change largely driving local flooding issues. St. Louis also now experiences 29 fewer days per year that drop below freezing, a trend that holds repercussions for local ecosystems and agriculture.

She also introduced the Climate Shift Index (CSI) tool, a way to communicate how much more or less likely a day’s temperature is due to climate change. While the current St. Louis temperatures may not be “strongly influenced” by climate change, the tool indicated St. Louis is in the yellow category, meaning it is one to two times more likely because of climate change. The CSI enables users to visualize temperature anomalies and what the temperature would have been without climate change, drawing interesting connections between current conditions and climate model predictions.

Finally, Dr. Dahl shared her own unexpected career path: Initially, she was committed to becoming a medical doctor specializing in premature infants and had applied as a pre-med student. As a last-minute registrant at a very large institution, few pre-med classes were available, leading her to enroll in an oceanography class out of necessity. She found herself fascinated by the “creative and beautiful ways of trying to understand Earth’s systems,” a single decision that ultimately changed the course of her life, shifting her focus from medicine to climate science.

The session concluded with Dr. Dahl’s advice to students: “Go to college and keep your mind open.”