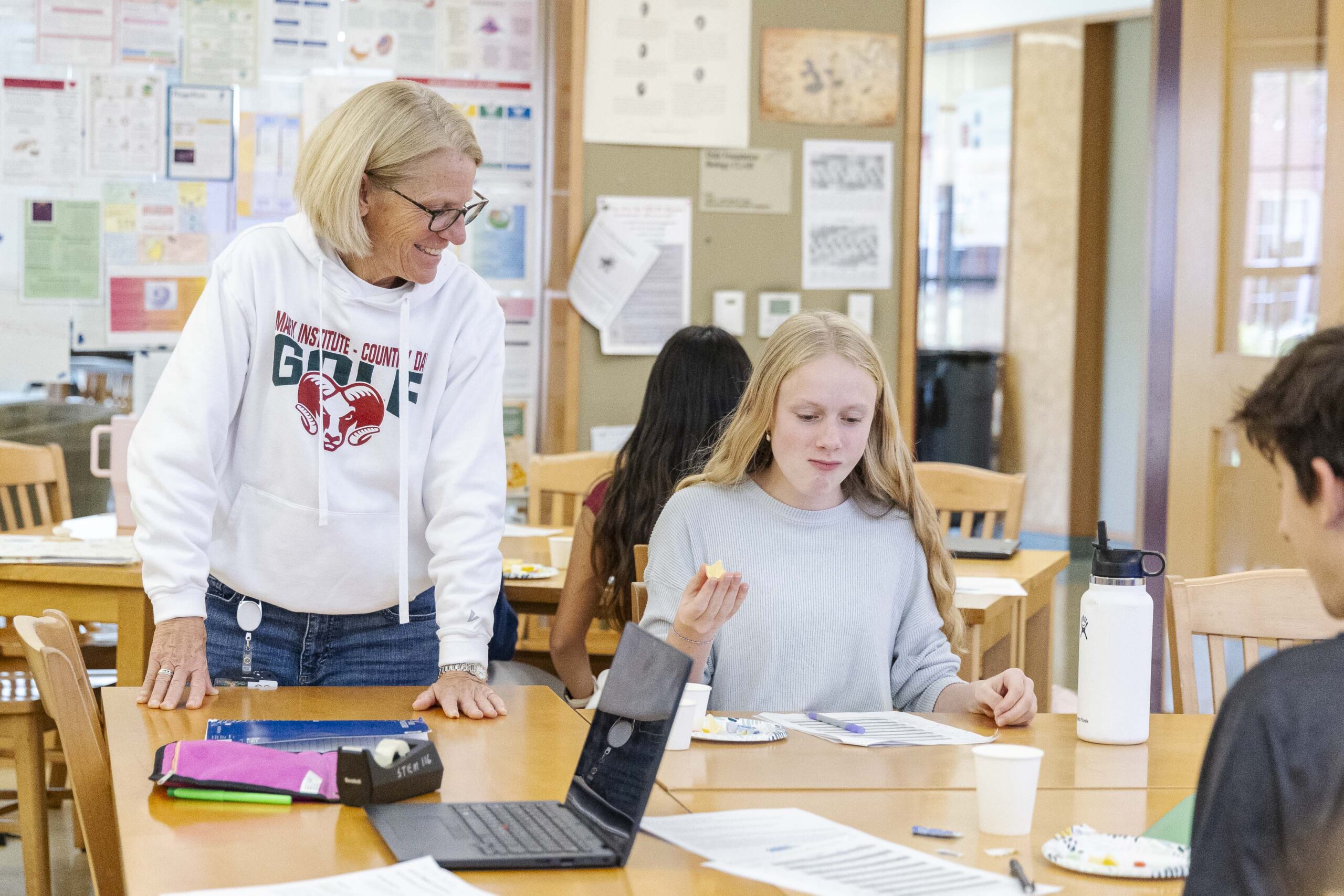

AP® classes are known for their rigorous schedules. Still, on a sunny day last week, our AP Biology and AP Psychology teachers, Dr. Christine Pickett, Rachel Tourais, Stephanie Matteson, and Diane Gioia, found time to bring their classes together for a colLABorative adventure. A taste-testing lab was set up for students to learn about the brain-body connection and explore the pairing of mechanical and perceptual aspects of taste.

The Biology Side: How We Taste

Your sense of taste, known as gustation, begins with a fundamental biological process called chemoreception, which involves sensing chemicals. The human tongue has tiny bumps called papillae, which hold special structures called taste buds. When you eat, food molecules called tastants dissolve in your saliva and enter the taste buds. Inside the bud, special cells act like sensors to detect these chemicals and immediately send a signal to your brain.

Humans can sense five primary tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami (also known as savory). Each of these tastes is triggered differently. For example, the sensation of “salty” comes from salt particles (sodium ions) entering the sensor cells. All five tastes can be sensed by the taste buds everywhere, and your brain blends those signals to create the complex flavors you actually experience.

The Psychology Side: Sensory Interaction

How the brain processes those signals into the complex experience we call flavor involves a key concept: sensory interaction. This process states that one sense can influence and even completely override another.

The most dramatic example of sensory interaction regarding food is the relationship between smell (olfaction) and taste (gustation). When you chew and swallow, food molecules travel up the back of your throat to the nasal cavity, where they are detected by scent receptors. All the complex, nuanced flavors, such as chocolate, cinnamon, or apple, come almost entirely from your sense of smell. And, this is why you can’t “taste” food when you have a bad head cold. The congestion blocks the nasal pathway to your smell receptors.

The Taste Lab

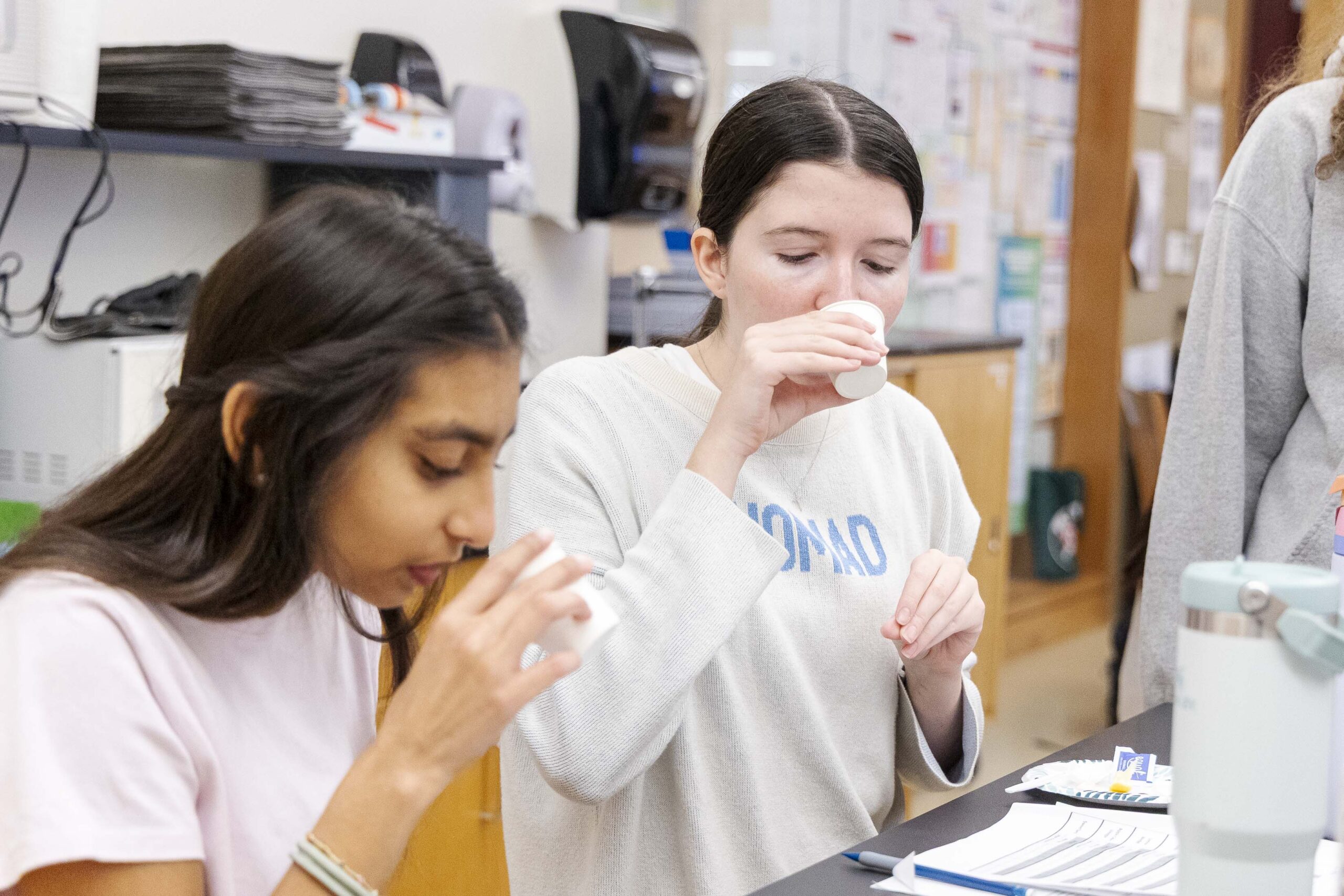

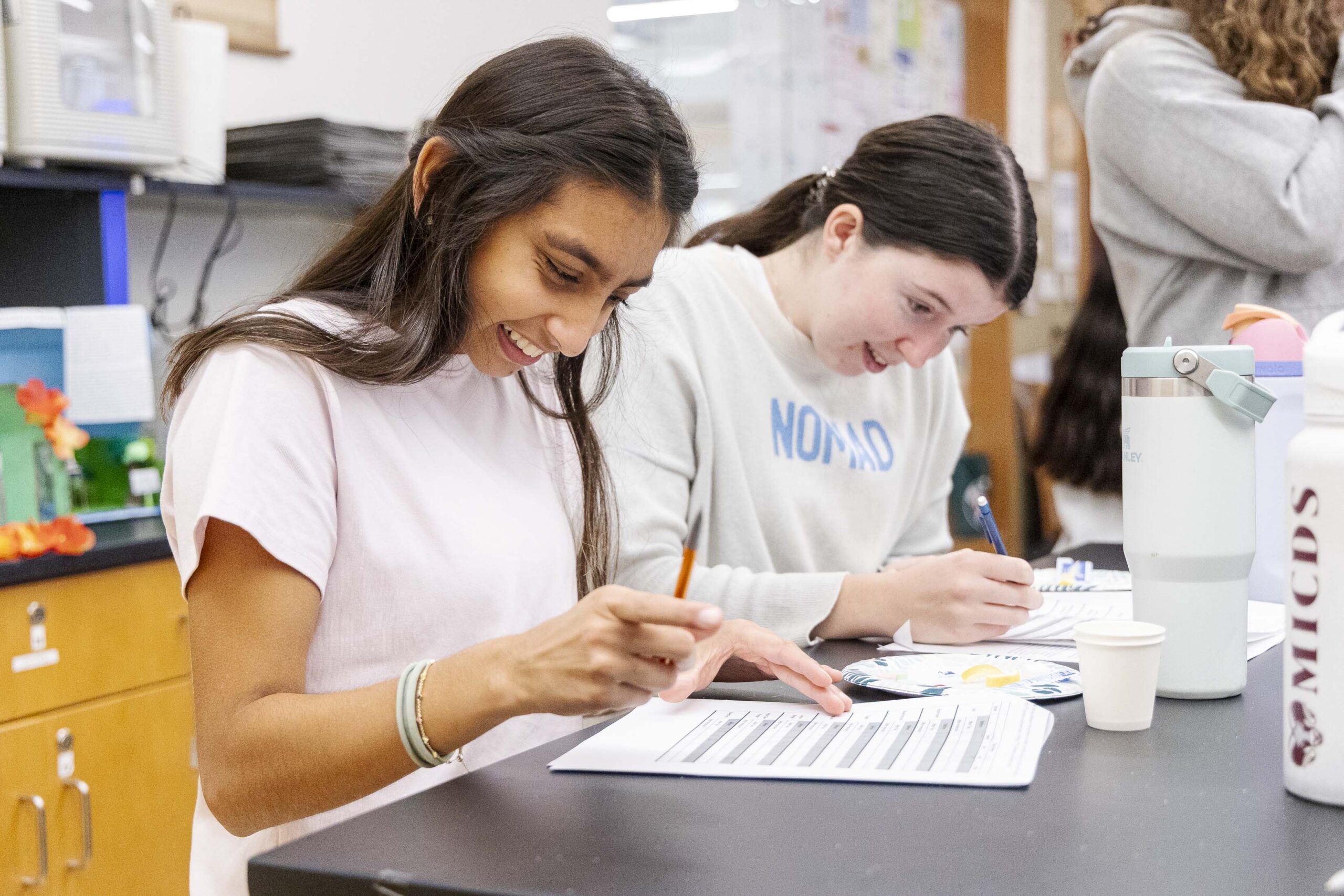

In the lab, biology and psychology students underwent two rounds of tasting to illustrate how our sense of taste can be dramatically manipulated. With some students apprehensive about the array of taste test items on the table and others raring to go, they all experienced a hilarious range of facial expressions as they rotated through the five primary tastes.

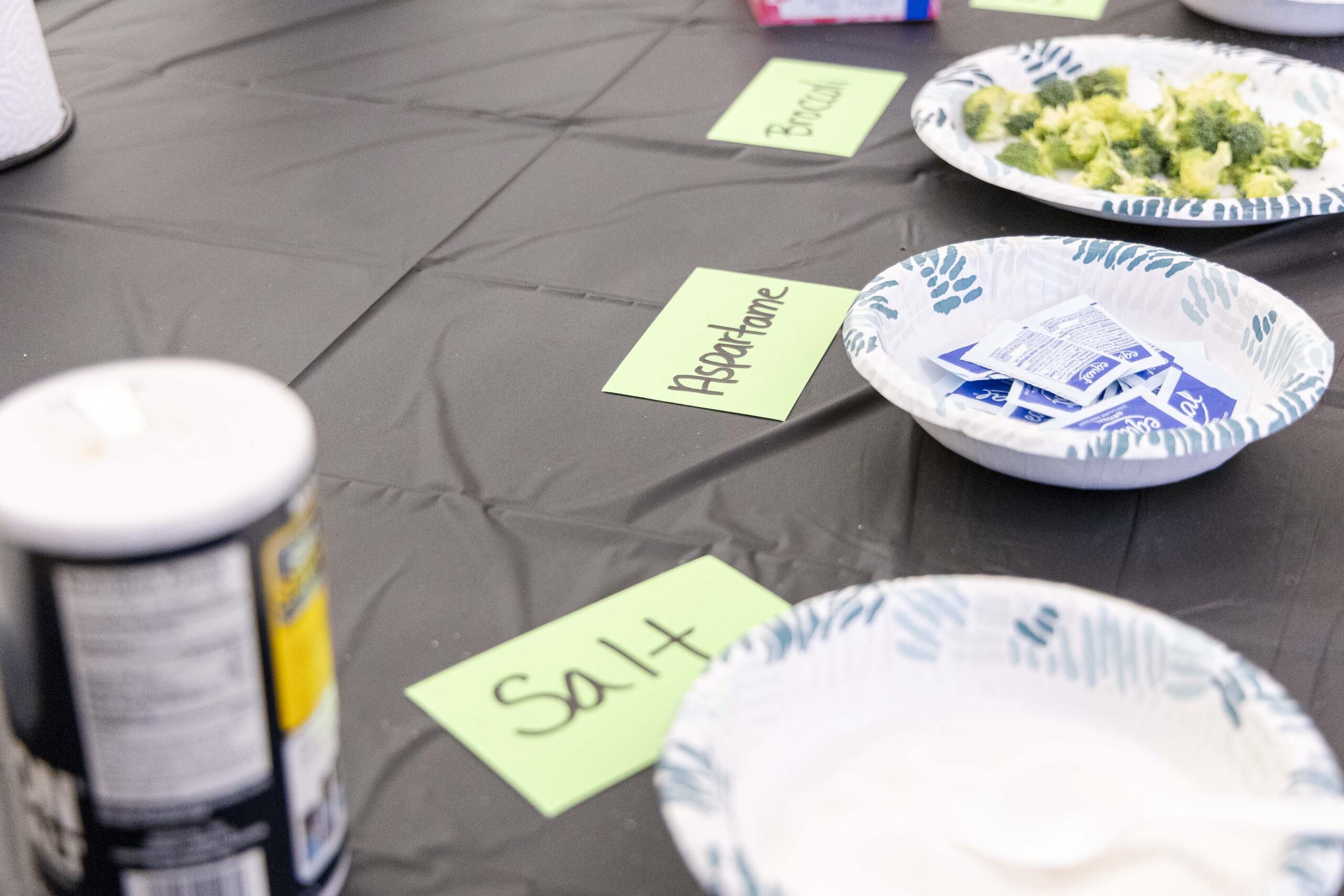

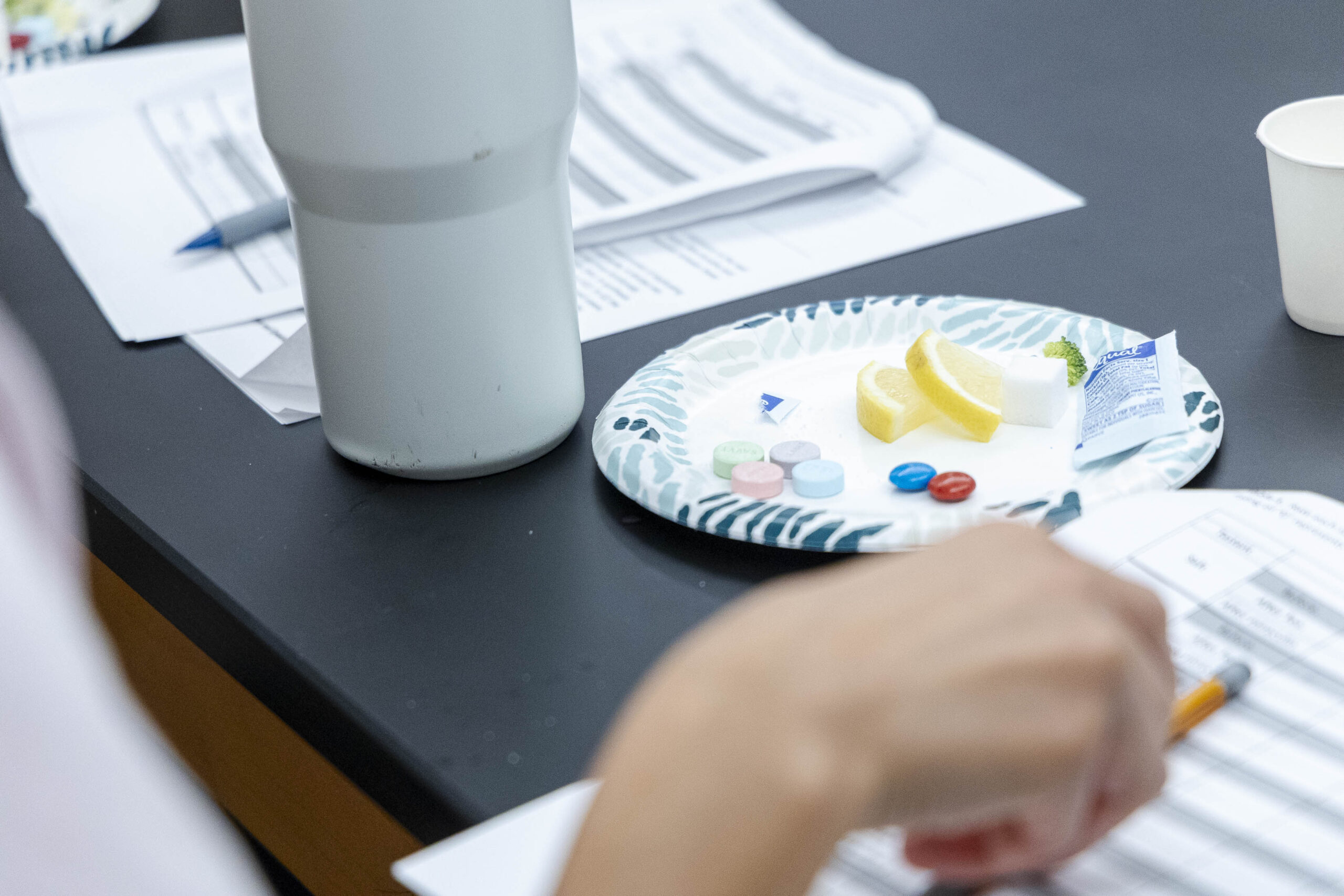

Round one included baseline tastes, during which students established their normal experience of the five basic tastes. Foods included were table salt, aspartame, raw broccoli, sugar, M&M®’s, a lemon wedge, apple cider vinegar, and SweeTarts®.

Round two came with a twist. Students were introduced to chemical agents that altered the way their taste buds functioned before eating the same foods again. Miraculin (found in the product Miracle Berries) is a protein that temporarily makes sour foods taste intensely sweet. The students soon reported that lemons tasted like candy. The other chemical agent was gymnema tea. This compound contains acids that bind to sweet receptors, temporarily blocking the ability to perceive sweetness. With the tea, students said that candies and sugar suddenly turned into flavorless grit in their mouths. They were amazed that removing just one chemical-sensing pathway completely changed their perception of food.

To further illustrate the smell-taste connection, Gioia and Matteson handed out Starburst candies. Students had to close their eyes and hold their noses before putting the Starburst into their mouths and then try to guess what flavor it was without the ability to smell the candy or see the color. Gioia said, “Students couldn’t consistently identify the flavor of the Starburst when they had their nose closed, but once they unpinched their nose, they could taste the flavor.”

Gioia then introduced how taste can be influenced by culture or experience. She handed out musk-flavored Lifesavers® candy for a final taste test. Musk is a common and popular flavor in Australia, where it is used in various products, including candy, ice cream, cake icing, biscuits, and tea. Gioia said, “In the United States, musk is a scent to us and not a flavor, so we notice the smell of it first, and the sweetness later. To many students, it was a very unpleasant taste. I had a student from Australia years ago who couldn’t stand our cherry flavor because it was associated with medicine. The lifesavers demonstrated that while taste buds are the same, ‘this is gross’ to ‘this is a delicacy’ lies all in perception.” Student reviews of the musk flavor ranged from “scented chalk” and “potpourri” to “deodorant” and “grandma’s perfume,” and some students even liked it!

The lab was a tasteful success, according to our students.

“I enjoyed that we got to compare two different ways of tasting the different foods, without any stimulus, and then with a stimulus. The worst thing I tasted was the raw lemon because I really hate sour tastes. What surprised me the most was how the tea and miracle berry actually worked, for example, how the berry was only activated in highly acidic pH levels to activate the sweetness taste receptors, and how the tea competitively inhibited the sweet taste receptors and eliminated their impact. This deepened my understanding because it taught me that a bunch of foods have very different tastes that different receptors pick up, and there are actually some times when some receptors won’t work because of something you eat, and something would taste different.” – Maahi Saini ’27 (AP Bio)

“I think the worst thing I tasted in the lab was the apple cider vinegar after I drank the tea. It wasn’t too bad the first time, but with the tea, it just tasted like pure salty bitterness.” – Grant Baumstark ’27 (AP Bio)

“I really enjoyed experiencing how my taste changes when inhibited. I drank the tea, which inhibited my sugar receptors, making things taste less sweet. The chocolate tasted like cardboard, and the aspartame tasted like dust, which was both sad and interesting.” – Lola Compton ’27 (AP Bio)

“I enjoyed experiencing the flavors of the foods before trying the tea and then comparing them to extremely different results afterward, because it showed me how much taste can be altered from specific foods. The apple cider vinegar was the worst for both trials because it had such a strong taste that wasn’t masked by the tea or the miracle berry. I was very surprised by how much the tea covered the taste of sweet things. When I tried the pure sugar after drinking the tea, there was almost no flavor, and I felt like I was eating sand because no taste came through. This made me think a lot more about how different receptors can be altered, but also the relationship between other senses and culture on our sense of taste. It is much easier to guess flavors when our sense of smell is not impacted, and some flavors that are appreciated in other cultures are unfamiliar and less enjoyable for people who are not used to them.” – Bella Anadkat ’26 (AP Psych)

“I really liked being able to do the lab in both AP Bio and AP Psych because it gave me a more well-rounded understanding of the material. It was also really fun to watch other people do it after I had already done it in one class. The thing that tasted the worst (this was definitely a universal opinion) was the apple cider vinegar. It tasted bad whether you had the tea or the miracle berry or not, but it was really cool to see how these things changed the taste. I’m glad I was able to learn the bio part of it because understanding how the receptors change was really interesting to tie into the psych information about sensation.” – Jackie Giljum ’26 (AP Bio & Psych)

“Last year, I did this lab as an AP Biology student, whereas this year I was in AP Psychology. I really enjoyed being able to do the same lab from a different scientific lens. I definitely was not a fan of the apple cider vinegar. I was surprised by how good the lemons tasted after the miracle berries! They tasted just like lemonade.” – Gigi Koster ’26 (AP Psych)

“What surprised me the most was that the gymnema tea made sugar taste like nothing at all. I wasn’t expecting that, and it completely caught me off guard. Overall, the lab deepened my understanding of taste by showing how taste receptors and neural pathways can be changed or blocked by certain foods and how those processes work together to create the flavors we perceive.” – Zoe Dickherber ’26 (AP Psych)

This lab was a fun and engaging adventure, proving to the students that taste is both a biological and psychological phenomenon.