If you don’t agree with me that McDonald’s is a wonderful place, I’m not sure we can be friends. Forget the menu for a minute (though you and I both know those fries are delicious) and focus instead on the setting in which it is served. Yes, fast-food restaurants “are bad, ecologically, economically, and calorically,” admits Adam Chandler in his book Drive-Thru Dreams, but they are also “matchbox chapels where there is practically no barrier to entry or belonging,” where “people of all sorts can sit and stay and stay and stay—at birthday parties, first dates, father-daughter breakfasts, Bible-study groups, teen hangs, and Shabbat dinners,” where “it’s easy to build rituals” because “everyone is welcome.”

In 1989, the sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third place” to describe the “great variety of public places that host the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work.” McDonald’s is—or at least it has traditionally been—just such a third place in American life. Institutions like these, Chandler writes, are “essential for civil society and civic engagement” and regrettably have “become rare in a country grappling with inequality and at a time when social encounters have gone heavily digital.” Oldenburg calls third places “levelers” that “counter the tendency to be restrictive in the enjoyment of others by being open to all” and “not confined to status distinctions current in the society.” In the parking lots and drive-thru lanes of fast-food restaurants nationwide, you will find BMWs and Nissans alike. Literally almost everyone in America eats at McDonald’s.

Since the pandemic, though, the way that we eat has changed. Walk inside a fast-food restaurant today and you may find it nearly empty. DoorDash and Uber Eats, both of which have partnerships with McDonald’s, now deliver five times as many meals to consumers as they did when Chandler published Drive-Thru Dreams in 2019. In an era of American life when our first places—our homes—are increasingly sorted and separated by income and social class, and our second places—our work environments—are becoming less inhabited if not entirely virtual, we are vacating our third places—our gathering places like McDonald’s—as well.

Though I seem to come across them more and more these days, I tend to be skeptical of comparisons of our contemporary American republic to the Weimar Republic of interwar Germany whose disintegration gave rise to Nazi dictatorship. For starters, our recent experience of inflation in the United States does not even begin to resemble the hyperinflation that devastated the German economy in the early 1920s; and the strength of our labor and stock markets today would have been the envy of Germany in the early 1930s, whose industrial collapse and widespread unemployment in the wake of the Great Depression brought misery to its population. Moreover, specters of military defeat and national humiliation do not haunt us as they haunted so many proud Germans after World War I; nor is there a modern-day Treaty of Versailles to whose punishing terms the United States is presently subject.

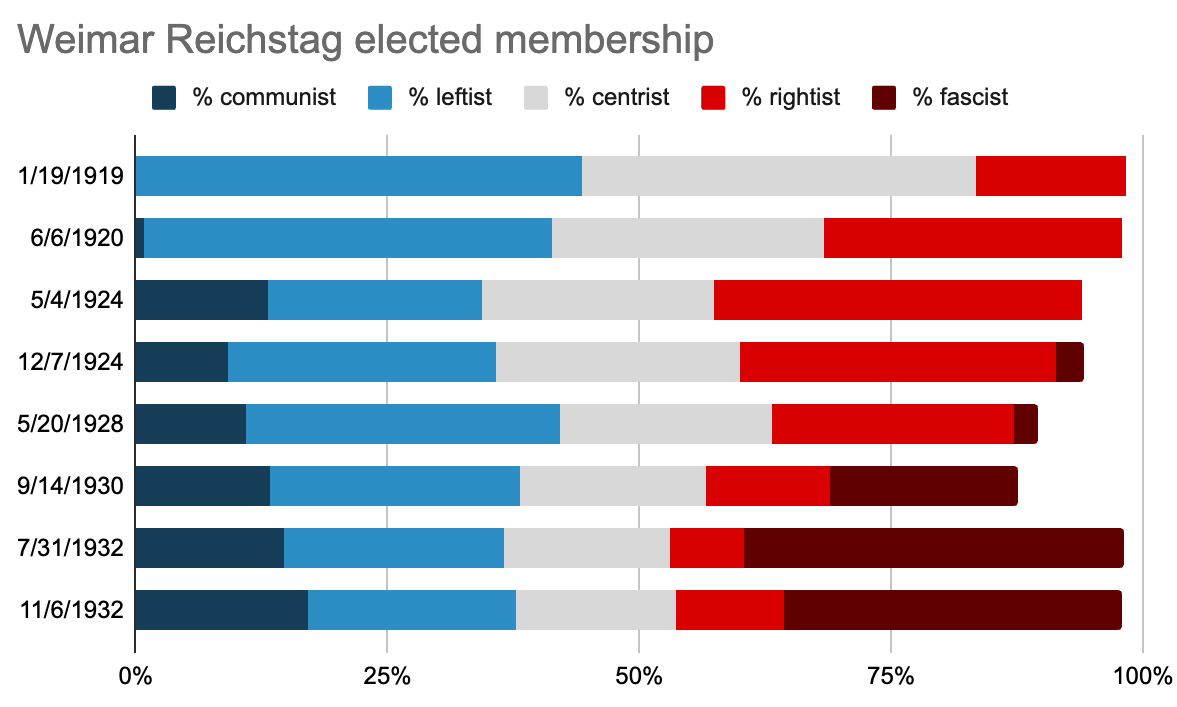

These differences being acknowledged, a phenomenon that does have my attention is the steady erosion of the political middle in our country not unlike that which transpired in interwar Germany. In January 1919, political centrists held 39% of seats in the Reichstag legislature, and not a single communist or fascist was elected. By November 1932, centrist parties held only 16% of seats, outnumbered by both the Communist Party of Germany, which held 17%, and Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which held 34%. Over the course of 14 years, average political sentiment had shifted only moderately, from center left to center right, but the polarization of the electorate and consequent disappearance of a political middle ground stalemated Germany’s government and provided a pretext for Hitler’s authoritarian ascendance—with terrible consequences for humanity.

Our two-party system in the United States is different, of course, but it doesn’t exactly build confidence to know that only 48 members of our House of Representatives—only about 11% of the total—are willing to be members of the centrist Problem Solvers Caucus. When did the middle become so unfashionable? Do we ever want solutions in America again, or do we only want problems? Because the frequency with which we lob epithets like “communist” and “fascist” at our fellow citizens across a generally abandoned zone of political compromise seems only to guarantee the latter, and to tempt an authoritarian fate.

We are committed to inhabiting the middle at MICDS, to building relationships and community and compromise across our differences. We are committed to being the kind of “third place” envisioned by Ray Oldenburg where “the charm and flavor of one’s personality, irrespective of his or her station in life, is what counts” and where “people may make blissful substitutions in the rosters of their associations, adding those they genuinely enjoy and admire”–in other words, make friendships, and experience belonging. Our Board and administration will continue to invest in our students at levels commensurate with our belief in their lifelong promise, and, as best we are able, help families—especially middle-income families, for whom tuition even after financial assistance can be so considerable a percentage of discretionary income—to afford that great investment. There is always more middle work to be done.

We are not quite McDonald’s at MICDS (though the french fries in our lunchrooms are delicious, too), but we do aspire to be a social “leveler” in our own way. In an ever more divided, isolated, and angry society, the project of gathering students from over 900 households across over 70 ZIP codes to learn and grow together “in the middle” feels more indispensable each day. How fortunate we are for this exceptional third place in our lives.

Always reason, always compassion, always courage. I wish you and your families a wonderful weekend.

Jay Rainey

Head of School

This week’s addition to the “Refrains for Rams” playlist is Holiday Inn by Elton John from his 1971 album Madman Across The Water (Apple Music / Spotify).