For most of human history, people have had to hunt and forage to meet their food needs. Hunting often required running after prey or hiding in trees, then carefully throwing weapons at prey as they tried to run away. But how does the human body allow a person to run, stand, hide, and throw? Seventh graders got to the bottom of it by immersing themselves in the mechanics of movement. They focused on the interdependent skeletal and muscular systems, aiming to build a hydraulic arm that replicates the human version.

Movement occurs when muscles contract and shorten, pulling on the bones. Critical to arm movement are the muscle pairs of biceps and triceps, the contractions and relaxations those muscles require, and the activation of the tendons to move the arm. For example, when picking up an object, the biceps muscle contracts, the triceps muscle relaxes, and the arm bends at the elbow. When you put the object down, the triceps muscle contracts and shortens, the biceps relax, and the arm straightens at the elbow.

This essential understanding in the classes of Middle School Science Teachers Nolan Clarke and Melody Gunn was just what the students needed before designing and building their own arm machine made of levers and pressure.

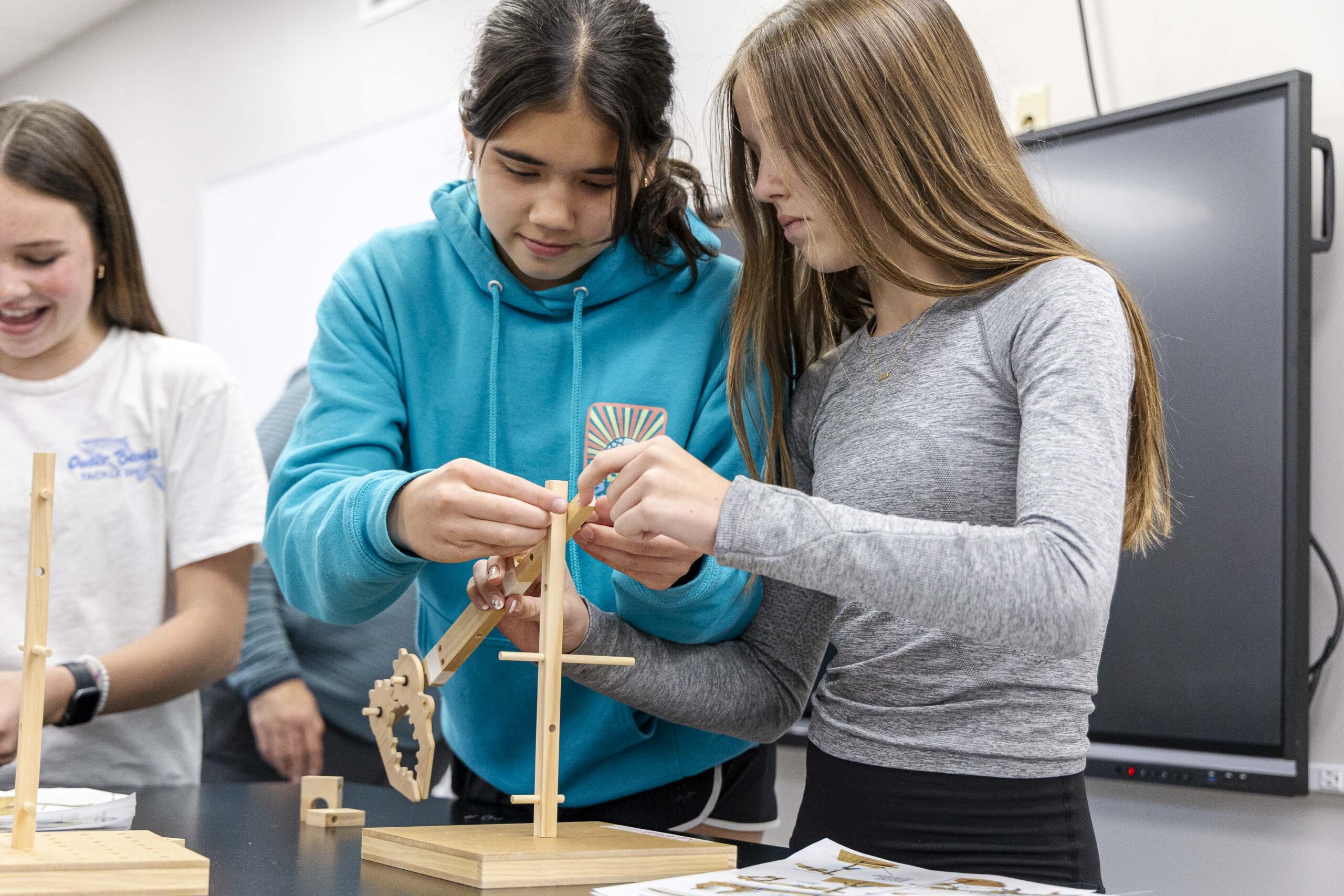

After a short instruction on how hydraulics work, the seventh-grade scientists divided into pairs to build arms that bend and straighten with a variety of provided wooden parts. From dowels and washers to gears and rubber bands, students had time to fiddle and tinker, gaining a deeper understanding of how each part of the bones and muscles of the arm, elbow, and hand works together. For the hydraulic portion, the young bioengineers used syringes filled with water and long tubes that connected to critical joints in the arm.

Many students worked through trial and error until it clicked, eventually getting their mechanical arms to function. Isaac Mba ’31 said, “One thing that surprised me was how many combinations worked. I thought finding the perfect one was the most challenging.”

Once students had a working hydraulic arm, they delivered presentations to demonstrate its functionality and the scientific principles behind their design.

John Plaxco ’31 found the project of learning how arms work very interesting. He said, “I never realized how much goes on in it, but learning with water and building was awesome. When we first built it, we had put the tube in the water, but then my teacher taught us how to make it work like a video game, and we made it so we could control it with tubes on the other side, so we didn’t need to hold it up.”

Way to flex, Rams!