The following letter is adapted from remarks delivered in two parts to the Upper School this week in Brauer Auditorium on Tuesday, April 23, and Friday, April 26.

Back in 2007, the year that 154 of you were born, I heard an interview with Andrew Gelman, a professor of statistics at Columbia University, following a Super Bowl at which, for the 10th consecutive year, the NFC team had won the game-opening coin toss over the AFC team. Dr. Gelman acknowledged that winning a 50-50 event 10 times in a row is indeed unlikely, but that it is less unlikely than we think. To give his own undergraduate students “an intuition into randomness,” he said, he introduces an activity in which he divides them into two groups and instructs one to record the results of 100 coin flips on the whiteboard and the other to create a fake sequence of 100 coin flips next to it. Upon returning to the room, he said, “I can immediately tell which is which. A real sequence of coin flips is likely to have a long run of heads or tails. A fake sequence tends to alternate too much between heads and tails, so I can immediately see the fake one looks too random and the real one looks like something strange went on.”

I have replicated Dr. Gelman’s sequence of coin flips today so that you can see for yourselves the frequent occurrence of long streaks with the same outcome, which become even more frequent and lengthier when you flip a coin, say, 10,000 times as opposed to just 100. I am sharing this demonstration with you as a reminder that there is such a thing as luck in our lives—good luck and bad luck alike—and that it frequently arrives in streaks. I am often reminded of the streakiness of luck when I watch you compete in sports. A good-luck streak can present itself as a series of unanswered goals, points, or hits, or personal bests in the pool or on the track. A bad-luck streak can show up as a run of points against you, easy shots missed, or close competitions lost.

Streaky luck is not limited to athletics, of course. In play, musical, or concert rehearsals, you might suddenly start forgetting your lines, or missing your notes, over and over again. In your academic life, you might encounter a series of concepts that you don’t initially understand, or you might receive a string of lower grades than you are used to getting. There’s a superstitious expression about streaks of misfortune—“bad things happen in threes”—but the truth is that bad things also happen in fours or fives, or eights or nines for that matter. So do happy things, of course, but we aren’t always tuned in to our streaks of good fortune. I don’t think I have ever heard anyone say, “Good things happen in threes.” Maybe we can make that “a thing”? (Wouldn’t that be fetch?)

Whether good or bad, the runs of luck that we experience in our lives are, at least to some degree, a function of random chance—and as random chance would have it, as I was preparing these remarks for you today, I received the following message from my mother on our family group text. (For context, I should note that my mother, like most members of our family, begins every morning playing word games on her phone.) “I’m having a fine day,” she announced. “Nine hours of sleep, Wordle in three, Waffle with five left, and four Connections in four tries. I think I’ll buy a lottery ticket.”

My mom was making a joke, of course, but maybe she was only half kidding? I think I would have only been half kidding if I were in her shoes. Her sentiment reflects the extent to which we seem almost programmed as human beings to believe that probability has a memory, and that a streak of luck, whether good or bad, is more likely to continue than to end—but it is not. Life is far more random at every turn, for better or for worse, than we want to believe.

There is a time-honored observation that you may have heard or read before: “The race is not to the swift nor the battle to the strong, nor does wealth come to the brilliant nor favor to the wise; but time and chance happen to them all.” These words appear in one of the Five Scrolls of the Ketuvim in the Hebrew Tanakh, which Christians call the Book of Ecclesiastes, but scholars have discerned influences of Buddhist, Ancient Persian, and Ancient Greek philosophy in the text as well, beyond its Judaistic origins; and I would be surprised if our forebears in ancient Chinese, Indian, African, aboriginal American, and other societies did not reflect in their own ways on the powerful role of luck in the human condition. This wisdom about “time and chance” affecting all people is more existential and eternal, I would suggest, than it is specifically religious and ancient, and the math of the coin toss—the math of Dr. Gelman’s classroom investigations into randomness—supports the essential truth of it.

However often, when viewed under a microscope, luck may exhibit streakiness, it exhibits equilibrium when viewed through a telescope. A sequence of 100 coin tosses regarded as a whole, no matter the extended runs of heads or tails it may beget along the way, is more likely than not to produce at least 46, and no more than 54, outcomes of each. (It should hardly surprise you that the repetition of a 50-50 exercise tends to yield 50-50 results over time.) You can witness these probabilities with me here, both microscopically and telescopically, in imagining first a single person flipping a coin 100 times alone and then 300 people flipping a coin 100 times in unison. A histogram of the latter—a telescopic view in graph form—reveals the extraordinary unlikelihood that anyone’s coin in that hypothetical group of 300 people would land heads fewer than 36 or more than 64 times in 100 flips.

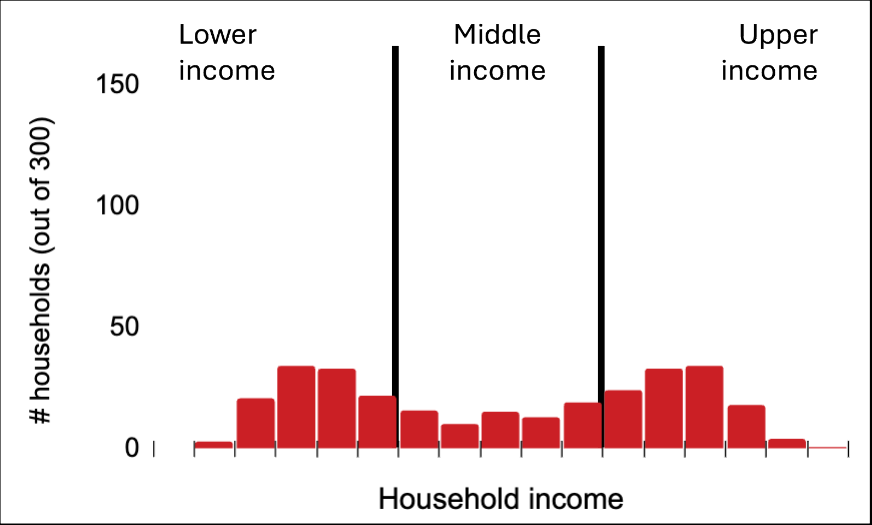

In 1968, two sociologists—Robert K. Merton and Harriet Zimmerman—described the combination of factors beyond random chance that explain social or economic success as “the Matthew effect of accumulated advantage,” a term inspired by a verse in the Book of Matthew in the Christian New Testament: “Whoever has will be given more; whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them.” It is easy enough to visualize the Matthew effect among our imagined population of 300 coin-flippers by applying a weighted coefficient to each otherwise random event so that an outcome of heads becomes more likely for someone who has landed heads already (“the rich get richer”) and an outcome of tails becomes more likely for someone who has landed tails already (“the poor get poorer”). If we further imagine the total number of heads as a representation of household income and adjust the Matthew effect coefficient accordingly—if we weight the coin to one side just so—we can approximate the distribution of lower-income, middle-income, and upper-income households in the United States as it existed in 1971, when middle-income households comprised a reasonably healthy 61% of the total:

For sake of argument, we could attribute the Matthew effect that explains the lower- and upper-income sections of this histogram entirely to human “internalities”—hard work, honesty, confidence, intelligence, self-discipline, and moral integrity, for example—since the proportion of middle-income households held relatively steady during the several decades between World War II and the 1970s. For simplicity, in other words, we could chalk up what we observe in the histogram above—the spread away from the middle—entirely to “luck and pluck.” (Respecting the latter, I am reminded of the very good advice offered to you recently from this same stage by one of our Distinguished Alumni, Linda Wells ’76, to “put yourself in the path of luck.”)

Presuming, however, that the percentage of human beings who are generally hard-working (or indolent), honest (or dishonest), confident (or timid), and so forth remains relatively constant over time, we must look to other phenomena—not to internalities but to externalities—to explain the expansion of the Matthew effect, and the corollary decline in the share of middle-income homes, that has transpired over the past 50 years. In the United States today, only about 50% of households constitute the middle class. Weight our figurative coin to one side a little more—increase the Matthew effect coefficient to reflect our contemporary reality—and the resulting depiction of income distribution further vacates the middle:

The Matthew effect externalities that propel socioeconomic separation include phenomena both explicit (laws, regulations, and financial capital, for instance) and implicit (such as cultural norms, personal networks, and social capital). Whatever their nature, their consequences are increasingly detrimental to American economic mobility and increasingly explanatory of our prevailing political discord. Because 2024 is an election year—and because all of you in the senior class and even some of you juniors will be eligible to vote in November—I should note how very differently our two main political parties understand the problem of a shrinking middle class that these histograms reveal. Republicans tend to cite trade agreements, illegal immigration, government overreach, and excess taxation as causal factors. Democrats tend to cite stagnating wages, labor union decline, corporate avarice, and societal inequities.

Notwithstanding these divergent points of view, solutions to our greatest challenges are always available when we have the courage to seek them together. I would implore you to involve yourselves in recognizing and endeavoring to slow, arrest, or even reverse the deleterious impacts of the Matthew effect in our midst, whether through electoral process participation, outreach to elected officials, volunteerism, or other forms of engagement. No modern nation, and certainly no democracy, can prosper without a thriving middle-class majority; and if middle-income household diminution persists or accelerates in the years ahead, the barbelled divide between “haves” and “have nots” in American life may become so wide as to be unbridgeable. The indefinite flipping of increasingly imbalanced coins might create an America that looks like this one:

I would also encourage you to assess the Matthew effect in your own lives. As I have aged, I have become more willing to admit that I have enjoyed—and that I continue to enjoy—any number of accidental personal, social, and professional advantages. I am White, male, straight, and tall, and I was raised in a loving, financially secure family that prioritized hard work and educational attainment. I earned none of these advantages myself, so increasingly I am trying to earn them, even though I never can nor will. The effort of doing so is liberating nonetheless.

What about yourselves? How is the Matthew effect propelling your own life? If you would suggest that it isn’t, I would remind you, respectfully, that you attend a selective (and very expensive) college-preparatory institution that aspires to a standard of excellence well beyond the reach, let alone the grasp, of most American families; that you are taught by exceptional teachers and cared for by dedicated staff and administrators; and that resources in support of your learning and growth abound. The Matthew effect involves all of us at MICDS. We must not construe it as a privilege we deserve, but rather accept it as a gift that we don’t—a gift that we must earn. To be in this community is no less an accident of my good fortune—my happy luck—than it is an accident of yours. I invite you to earn it with me.

Always reason, always compassion, always courage. My best wishes to you and your families for a joyful weekend ahead.

Jay Rainey

Head of School

This week’s addition to the “Refrains for Rams” playlist: God Bless the Child by Billie Holiday, the seventh track on her 1956 album Lady Sings The Blues. “Them that’s got shall have. / Them that’s not shall lose. / So the Bible said, and it still is news. / Mama may have, Papa may have, / But God bless the child that’s got his own, that’s got his own.” (Apple Music / Spotify)